Mesonephric adenocarcinoma arising from the uterine corpus: case reports and literature review

Highlight box

Key findings

• The tumors of the three cases finding mesonephric remnants around the mesonephric adenocarcinoma (MNAC) cells were all arising from the myometrium layer, without endometrium involved, and the myometrium subgroup had a higher elevated CA125 and poorer prognosis than the endometrium group.

What is known and what is new?

• To date, only a few cases of MNAC arising from of the uterine body (UB-MNAC) have been reported and the histogenesis of UB-MNAC is not yet clear.

• Besides one case in the reported literature, it is the first time that find mesonephric remnants around the UB-MNAC cells in our two cases. Besides the histogenesis difference, the two subgroups have different clinical prognosis.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• We propose two different pathways by which MNAC arises in the uterine corpus: (I) for those tumors arising from myometrium, it is directly developing from the mesonephric remnants and/or (II) for those originating from the endometrium, it is due to mesonephric transformation of Müllerian adenocarcinoma. And the two subgroups might have different clinical prognosis. In our daily work in the future, we need pay more attention to this kind of tumors, and collect more relevant data to prove our hypothesis and guide relevant clinical treatment.

Introduction

Background

Mesonephric adenocarcinoma (MNAC) is a rare carcinoma that originates from mesonephric remnant of the female genital tract (1-3), and are predominantly located on the lateral walls of the cervix and vagina (4). Of the cases reported to date, the vast majority of MNAC are from uterine cervix (1,2,4-19), comprising <1% of all carcinomas at this site (20), several cases of MNAC are from ovary (21-24), and rare cases are from vagina (4,7,25-29) and uterine corpus (4,11,21,30-43).

MNAC is typically characterized by a combination of diverse growth patterns in histopathology, including tubulocystic, glandular, papillary, retiform, and glomeruloid architecture. Dense eosinophilic secretion is usually present in the tubulocystic components (6). MNAC has a distinctive immunophenotype, it usually exhibits positive immunoreactivity for GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3), paired box 2 (PAX2), CD10, TTF1, and negative reactivity for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) (39,44,45).

Mesonephric-like carcinomas (MLAC) are a series of tumors that recently described by McFarland and colleagues. They reported a subset of 5 ovarian and 7 uterine corpus neoplasms which presented the typical histologic features of mesonephric carcinomas, but mesonephric remnants could not be found around it. Furthermore, some tumors were only confined to the endometrium layer without deep myometrium involved, where mesonephric remnants would exist theoretically. These tumors exhibited an immunophenotype same as mesonephric carcinomas, which were variably positive for CD10, calretinin, GATA3, and TTF1, but negative for ER and PR. Although the authors presume that these neoplasms might represent a new type of endometrioid adenocarcinomas, considering the immunohistochemical and histologic characteristics they found, they were in favor of that these tumors were “true” mesonephric neoplasms but admitted the uncertainty in their pathogenesis, so they termed them as “mesonephric-like” adenocarcinomas (21). Molecular analyses suggest that MLACs are characterized by recurrent KRAS-mutations as well as unique immunohistochemical features and an aggressive clinical course (24,44,46). One research demonstrated that PIK3CA mutations, which have not previously been identified in cervical MNAC, were found in 3 of 7 (43%) MLAC in uterine corpus, and thus raised the question about possible Müllerian origin of the uterine corpus MLAC (46).

Rationale and knowledge gap

According to the published reports, the distant metastasis (5%) and recurrence rate (32%) of MNAC arising from the uterine cervix (UC-MNAC) is substantially higher than that of FIGO stage I cervical squamous cell carcinoma (11.0%) and usual-type endocervical adenocarcinoma (16.0%), suggesting that patients with UC-MNAC have a worse prognosis than those with more common types of cervical carcinoma (13). But because of the limited number of cases reported, less is known regarding the clinical outcomes of UB-MNAC. Most publications on UB-MNAC are individual case reports or case series (4,11,21,30-43). A recent case series reported 11 cases of UB-MNAC, by investigating the clinicopathologic details, they concluded UB-MNAC displays an aggressive biological behavior, with a tendency to metastasize to the lungs (39). But still, little is known about UB-MNAC, and it remains debated whether they represent mesonephric carcinomas arising in the uterus or Müllerian carcinomas that undergo mesonephric transformation.

Objective

These findings led us to investigate UB-MNAC cases diagnosed in our institution and reviewed the published MNAC and MLAC arising from the uterine corpus, summarized and analyzed the characteristics of them. In this study, we presented three UB-MNAC cases diagnosed in our hospital, adding cases of UB-MNAC with morphologic and immunohistochemical analyses to the existing literature and to provide more data regarding clinical characteristics of UB-MNAC, hoping to help the clinician and pathologist have a better understanding of this rare carcinoma. And by presenting two special UB-MNAC cases, which mesonephric remnants were found around the corpus tumor for the first time, we add more evidence to better understand the pathogenesis of UB-MNAC. We present this study in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-23-21/rc).

Case presentation

Totally three patients of UB-MNAC were selected according to the diagnosis criteria, they were treated and monitored at the Gynecologic Department, West China Children and Women Hospital (Sichuan, China). We thoroughly reviewed patients’ medical records, pathology reports, and gross photographs. Clinical details, including age at initial diagnosis, presentation of symptoms and/or signs, serum cancer antigen-125 (CA125) level, preoperative endometrial curettage diagnoses, surgical treatment, FIGO stage, postoperative treatment, development of metastasis, overall survival, and current status were examined (summarized in Table S1). The pathologic characteristics reviewed included tumor size, architectural pattern, and originate location; presence of sarcomatous component and so on.

Case 1

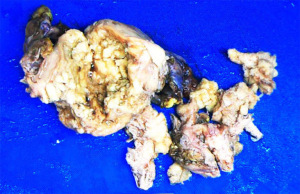

A 67-year-old patient with past medical history of hypertension presented with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding and cough for one week. Transvaginal ultrasound and MRI examination revealed a hyperechoic endometrial mass in the cavity. Dilatation and curettage were performed and the mass was diagnosed as endometrial carcinoma with mixed clear cell and endometrioid components. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography indicated metastatic lesion in the lung and the pubic bone. The patient then underwent total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, appendectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Grossly, a 9.0 cm × 6.0 cm × 3.5 cm solid mass was located in the fundus protruding into the uterine cavity (Figure 1). Cervix and bilateral adnexa were unremarkable. Omentum and lymph nodes were grossly normal. Microscopically, the tumor exhibited a variety of growth patterns, including a characteristic tubular pattern with dense eosinophilic secretion, as well as a variety of morphologies, such as acinar, papillary, and ductal structures. The mass infiltrated into the outer half of myometrium, and was limited to the uterus with no serosal or cervical involvement, but lymphovascular space invasion was found. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that the tumor cells were immunoreactive for GATA3, CD10 (luminal), TTF-1, PAX8, p16 (patchy), and PTEN, and negative for ER, PR, AR, WT-1, P53, HNF1-β. The mismatch repair gene PMS2, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 function retained well. All submitted lymph nodes were negative for carcinoma. The patient was diagnosed as stage IVB UB-MNAC, and she received postoperative systematic chemotherapy (Paclitaxel 240 mg and carboplatin 550 mg, ivgtt), and had no evidence of disease recurrence for 3 months after the surgery by now.

Case 2

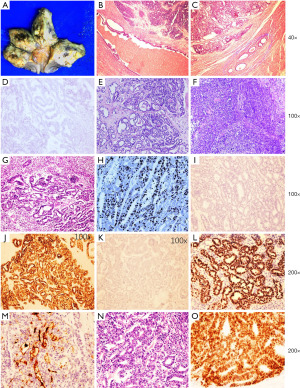

A 55-year-old postmenopausal patient with unremarkable medical history complained of pink vaginal discharge, pollakiuria, and bilateral hip joint pain for several weeks. The ultrasound and CT scan revealed a 11 cm × 11 cm × 9 cm heterogeneous hyperechoic mass in the posterior and fundal region of the uterus, with vague borderline. The CT scan also indicated metastatic lesion in the lung and right ischium. The para-aorta lymph node was enlarged. Laboratory workup showed a significantly increased CA125 level of 145.1 IU/ML (normal range of CA125 is 0–35 kU/L). She received D&C and the pathologic result indicated poor to moderate differentiated adenocarcinoma. Then she was given three times neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Paclitaxel 240 mg and carboplatin 500 mg, ivgtt), and total laparotomy hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was performed later. Gross examination revealed a 11.0 cm × 7.0 cm × 7.0 cm ill-defined hemorrhagic mass lesion located in the myometrium of the posterior wall of the uterus (Figure 2). The mass grossly involved the serosa and the right sacrum ligament., the bilateral adnexa were totally normal. The endometrium and cervix were grossly normal too. Intraoperative frozen section was diagnosed as poorly differentiated cancer or carcinosarcoma, needing immunohistochemistry (IHC) to identify. Microscopically, the mass showed a variety of growth patterns, including tubulocystic, papillary, solid, and retiform structures (Figure 2). Densely eosinophilic secretions were focally present in the tubular and ductal structure of the tumor. The tumor cells penetrated beyond serosa and involved the right ovary as well as the lymphovascular system. Notably, normal mesonephric remnant was found around the adenocarcinoma cells. The entire endometrium was submitted for microscopic examination and showed focal pure hyperplasia and small focal complicated hyperplasia. Uterine cervix and the rest dissected part were negative for carcinoma. Immunohistochemical stains were performed, and indicated that the adenocarcinoma component was positive for GATA3, CD10 (luminal), TTF-1, PAX2, PAX8, p16 (patchy), PTEN, CK-P, CK7, β-catenin and CyclinD, negative for ER, PR, Napsin-A, CD15, HNF1-β, Vimentin, caldesmon, Des, SMA, and WT-1, the Ki67% proliferation index was about 80%. The spindle cells component was negative for ER, PR, CK-P, CK7, EMA, CD10, CyclinD1, α-Inhibin, TTF-1, Des, caldesmon, GATA3, Pax-2, and positive for Vimentin, SMA, Pax-8 (focal), and the Ki67 proliferation index was about 20%. A diagnosis of stage IVB UB-MNAC was made, including a small component of spindle cells, which partially showed leiomyosarcoma differentiation. At the most recent follow-up, the patient was scheduled chemotherapy (Ifosfamide 2 g, Cisplatin 30 mg, Bevacizumab 400 mg and Pamidronate disodium 30 mg, ivgtt), and showed no signs of recurrence for 4 months.

Case 3

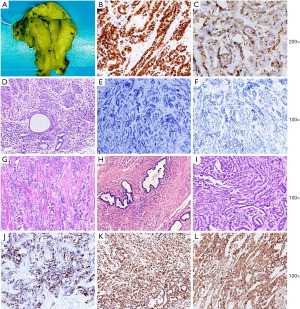

The patient was 75 years old, and she received a laparoscopic salpingo-oophorectomy due to benign adnexal cyst several years before. The routine ultrasonography follow-up indicated a mass in the right wall of the uterus. The further CT scan showed a cystic-solid mass in the right adnexal region, which had no clear margin to the uterine wall. No other abnormality was found by the imaging test, and the CA125 level was also normal. A totally hysterectomy and abdominal multipoint biopsy was performed on her. The gross finding was a partial cystic partial solid mass measuring about 5 cm in diameter in the right cornu of the uterus. The adenocarcinoma was arising from the myometrium layer of the right uterine cornu, invaded the serosal layer, and formed a mass in the right adnexal region. The endometrium was totally not affected. Noteworthy, mesonephric remnant was found around the adenocarcinoma cells. Metastatic lesion was found on the intestine surface. The adenocarcinoma was immunoreactive for GATA3, CD10(luminal), TTF-1, PAX2, PAX8, p16(patchy), CR (partial) and PTEN, and negative for ER, PR, WT-1, P53, AR, CK-20, CEA, CD56, Syn, CgA, α-Inhibin, Ki67 proliferation index was about 60% (Figure 3). The diagnosis for this patient was FIGO stage IVB UB-MNAC, and she received systematic chemotherapy after surgery (Docetaxel 80 mg ivgtt and Cisplatin 80 mg i.p, totally 6 times). She was monitored in our hospital for 17 months by now, showing no signs of recurrence.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013) and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Second University Hospital under No. 2022(047). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

MNAC is a typical rare malignancy which arises from the mesonephric remnant located in the female genital tract (1). It was found mostly in the cervix (3) and rarely in the vagina (26) and uterine corpus (31). These carcinomas have unique histologic and immunohistochemical characteristics. MNAC often presented variable histologic grown patterns from microscopic field to field within the same tumor, and as a result may be under-evaluated and misdiagnosed (4). The characteristic morphologic pattern includes tubulocystic, retiform, papillary, ductal, sex cord, glomeruloid and solid components, the lumens contain dense periodic acid Schiff positive eosinophilic secretions (9,11,35). Due to its rarity, these histologic patterns can easily be mistaken for a variety of other neoplasms to the unsuspecting pathologist. There may be a characteristic immunophenotype with consistent positive staining for GATA3 and PAX-8 as well as negativity staining for steroid hormone receptors, both the ER and PR (39,44,47). The staining for TTF1 is usually diffuse, and there is a luminal positivity for CD10 in the majority of cases (48).

UB-MNAC is rare, and the diagnosis of UB-MNAC can be challenging, especially on biopsy materials and frozen sections. Morphologic differential diagnoses of UB-MNAC include cervical MNAC with involvement of the uterine corpus and different morphological subtypes of endometrial adenocarcinomas. The distinction of a “true” cervical MNAC depends on the tumor being located entirely or predominantly within the cervix or the uterine corpus. This can be determined by a detailed analysis of the hysterectomy specimen or preoperatively by a topographic evaluation of the imaging findings on CT and/or MRI (21). To distinguish the UB-MNAC from other types of endometrial adenocarcinomas, such as clear cell carcinoma, endometrioid carcinoma, serous carcinoma, the characteristic grown pattern mentioned above and the classic immunohistochemical stains should be considered together. But by now, there are no antibodies that can distinguish UB-MNAC from Müllerian carcinomas.

The question about a real UB-MNAC has been raised by McFarland et al., who described a series of corpus mesonephric-like adenocarcinomas (MLAC) arising in the endometrium and infiltrating into the myometrium (21). Beside in the uterine body, some cases of mesonephric carcinomas of ovary have been reported to show a sarcomatous component and have been defined as “mesonephric-like carcinosarcomas”, characterized by poor prognosis and high metastatic behavior (49).

To better understand this, we reviewed all the published cases of UB-MNAC or MLAC, and summarized them in Table S1. As shown in Table 1, totally, 53 cases of UB-MNAC or MLAC, including the present three cases, have been reported by now, but only 47 patients had detailed clinical information. Generally, the patients with UB-MNAC or MLAC ranged in age from 31 to 91 years (mean, 59.8 years). The tumors measured 1.5 to 9.0 cm (mean, 5.3 cm) in size. Most of the patients complained of vaginal bleeding (27, 58.4%). Nine cases showed an elevated CA125 level, accounting for 19.6%, while the other 16 cases had a normal CA125 level. Twenty-three cases (50%) were FIGO stage I, 5 cases (10.9%) were stage II, 10 cases (21.7%) were stage III, and 7 cases (15.2%) were stage IV. Only 7 cases were diagnosed as MNAC by D&C before operation, while 12 cases (26.1%) had been mistaken as EC. They all received operation therapy, but exact operation varied from TH + BSO to TH + BSO + PLND + PALND, depending on the stage and the patient general well beings. Twenty cases, that was 43.4%, received postoperative therapy, either chemotherapy or radiotherapy or both. Fifteen cases (32.6%) showed metastasis, usually to lung (12 cases, 26.1%). Among them, 30 cases are arising from the endometrium, and/or infiltrating into the myometrium layer, accounting for 65.2%, while other 10 cases (21.7%) were completely confined in the myometrium layer, without endometrium involved. Respectively, evidence of mesonephric remnant was only found in 3 (6.5%) cases, with two cases in our hospital found mesonephric remnant around the tumor, and the other one found mesonephric remnant in the cervix (summarized in Table S1). Notably, the tumors of the three cases were all arising from the myometrium, without endometrium involved. These three cases, especially the two cases in our hospital, which found mesonephric remnants around the tumor raised our interesting about whether these mesonephric or mesonephric-like adenocarcinomas arising from different parts of the uterine corpus have the same pathogenesis.

Table 1

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Total number | 46 |

| Age (years) | 59.8 [31–91] |

| Symptoms | |

| Vaginal bleeding | 27 (58.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (4.3) |

| Pollakiuria | 1 (2.2) |

| None | 2 (4.3) |

| NA | 16 (34.8) |

| CA125 | |

| Elevated | 9 (19.6) |

| Normal level | 16 (34.8) |

| NA | 21 (45.7) |

| Size (cm) | 5.3 [1.5–9.0] |

| Stage | |

| I | 23 (50.0) |

| II | 5 (10.9) |

| III | 10 (21.7) |

| IV | 7 (15.2) |

| NA | 1 (2.2) |

| D&C | |

| MNAC | 7 (15.2) |

| EC | 12 (26.1) |

| AC | 2 (4.3) |

| CS | 2 (4.3) |

| None | 2 (4.3) |

| NA | 21 (45.7) |

| Location | |

| Myometrium | 10 (21.7) |

| Endometrium, myometrium involved | 30 (65.2) |

| NA | 6 (13.1) |

| Operation | |

| TH | 1 (2.2) |

| TH + BSO | 8 (17.4) |

| TH + BS0 + PLND | 6 (13.0) |

| TH + BSO + OMT | 1 (2.2) |

| TH + BS0 + PLND + PALND | 12 (26.1) |

| TH + BS0 + PLND + PALND + OMT | 1 (2.2) |

| TH + BS0 + PLND + PALND + OMB | 1 (2.2) |

| TH + BSO + PLND + PALND + OMT + APD | 1 (2.2) |

| NA | 15 (32.6) |

| Post operation therapy | |

| None | 9 (19.6) |

| CT | 11 (23.9) |

| RT | 3 (6.5) |

| CT + RT | 6 (13.0) |

| NA | 17 (37.0) |

| Metastasis | |

| None | 15 (32.6) |

| Lung | 12 (26.1) |

| Lymph node | 3 (6.5) |

| NA | 16 (34.8) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean [range]. UB-MNAC, uterus body mesonephric adenocarcinoma; MLAC, mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma; NA, not available; D&C, dilatation and curettage; EC, endometrioid carcinoma; AC, adenocarcinoma; CS, carcinosarcoma; TH, total hysterectomy; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection; PALND, para-aorta lymph node dissection; OMT, omentectomy; OMB, omental biopsy; APD, appendectomy; CT, chemotherapy; RT, radiotherapy.

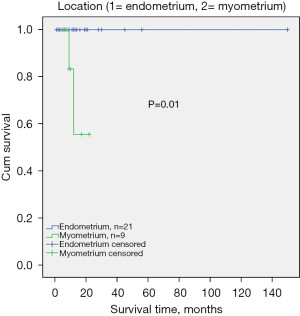

To have a better understanding of this, we further analyzed the clinical characteristics and the survival rate of the two subgroup cases. Known that the MLAC arising from the endometrium had identical morphologic and immunohistochemical features with the UB-MNAC as the published literature indicated (21), our analyzed results showed the two subgroups most clinical characteristics were also identical (Table 2), such as the age (60.6±1.8 and 55.2±4.3, P=0.19), symptoms (most cases were presented with vaginal bleeding), stages (P=0.61), and metastasis rate (P>0.99)and metastasis site (a tendency to metastasize to the lung). Notably, 81.3% cases rising from the endometrium had normal CA125 level, while those originating from the myometrium had a higher elevated CA125 level (P=0.03). This result was in consistent with the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, which indicated that the cases from the myometrium layer had a poorer prognosis (Figure 4, P=0.01). But this need more data, because the longest follow-up time was only 56 months as reported and the cases were limited so far.

Table 2

| Clinical characteristics | Tumor originate location | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrium (n=30) | Myometrium (n=10) | ||

| Age (years) | 60.6±1.8 | 55.2±4.3 | 0.19 |

| Stage | 0.61 | ||

| I | 18 (60.0) | 4 (44.4) | |

| II | 3 (10.0) | 2 (22.2) | |

| III | 6 (20.0) | 1 (11.1) | |

| IV | 3 (10.0) | 2 (22.2) | |

| CA125 | 0.03* | ||

| Normal | 13 (81.3) | 3 (33.3) | |

| Elevated | 3 (18.7) | 6 (66.7) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.25 | ||

| ≤5 | 16 (66.7) | 4 (40.0) | |

| >5 | 8 (33.3) | 6 (60.0) | |

| Therapy | 0.08 | ||

| Operation | 8 (42.1) | 1 (10.0 | |

| Operation + others | 11 (57.9) | 9 (90.0) | |

| Metastasis | >0.99 | ||

| Yes | 10 (47.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

| No | 11 (52.4) | 5 (55.6) | |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± SD. *, means statistically significant difference. UB-MNAC, uterus body mesonephric adenocarcinoma.

By reviewing the literatures, we found that some theories do exist for the MLAC, one is the secondary trans-differentiation from Müllerian type carcinomas. The theory appears to be supported on a molecular basis. In the first sizeable series investigating the molecular alterations in MNAC, the authors showed that MLAC, similar to MNAC, are characterized by recurrent KRAS mutations, frequently PIK3CA mutations, and lack of PTEN mutations. PIK3CA mutations are mutations which have not been identified in MNAC previously (46) and PTEN and PIK3CA mutations are common in endometrial carcinomas, present in up to 95% of endometrial microsatellite instable and POLE mutated tumors (44). These molecular features demonstrate biological overlap with carcinomas of both mesonephric and Mullerian (endometrioid) differentiation. Besides, one recent report presented a patient with coexisting endometrial MLAC and low-grade endometrioid carcinoma (40), which was treated using medroxyprogesterone acetate therapy, resulting in recurrence of MLAC alone. Another recently published two papers presented two ovarian adenocarcinomas with combined low-grade serous and mesonephric morphologies, also suggest a Müllerian Origin for some Mesonephric Carcinomas (22,24). Given the previously documented association with endometriosis (ovarian neoplasms) (24) and the prominent endometrial involvement (uterine corpus neoplasms) (21), these tumors are best regarded as of Mullerian origin and representing adenocarcinomas which differentiate along mesonephric lines.

Strengths and limitations

From the cases we presented in this study, we suggest that UB-MNAC arising from different part of the uterus have different pathogenesis, and may have different prognosis though they may have identical morphology and immunophenotype as well as other clinical characteristics. The tumor arise from the myometrium should be referred as “true” mesonephric carcinomas which is originated from the mesonephric remnant in the uterine wall, though in most cases, mesonephric remnants could not be found. That may be because of the overgrowth of the tumor. and those located in the endometrium layer are better to be diagnosed as “mesonephric-like” carcinomas, which may undergo mesonephric transformation of Müllerian adenocarcinoma. To date, only 53 cases of UB-MNAC or MLAC, including the present cases, have been reported. It might because many cases had been misdiagnosed as Müllerian adenocarcinoma. To better understand the pathogenesis and biological behavior, it is necessary to collect sufficient MNAC cases for clinicopathological and molecular study by keeping in mind the possible presence and classic histological features of MNAC or MLAC in the uterine corpus.

Conclusions

We described three cases of UB-MNAC in our hospital. Among them, two cases were completely confined within the corpus myometrium, without endometrium involved. And typically, mesonephric remnant was found around the tumor in the two cases. From our knowledge, it is the first time that find mesonephric remnants around the UB-MNAC cells, which has profound meaning for our understanding of the histogenesis of UB-MNAC. While the histogenesis of MNAC has not yet been confirmed in the uterine corpus, we propose two different pathways by which MNAC arises in the uterine corpus: (I) for those tumors arising from myometrium, it is directly developing from the mesonephric remnants and/or (II) for those originating from the endometrium, it is due to mesonephric transformation of Müllerian adenocarcinoma. Meanwhile, though limited information, by analyzing the two subgroups in the published literatures, we found that the two subgroups might have different clinical prognosis, which might further more support our hypothesis of the two different originations for the UB-MNAC and MLAC. Most important, better understanding of the histogenesis for the UB-MNAC and MLAC could fascinate the treatment and rehabilitation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of West China Second University Hospital Pathologists’ Conference for discussing the cases.

Funding: This study was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-23-21/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-23-21/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-23-21/coif). All authors report that this study was supported by the Key R & D Projects of Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (No. 2022YFS0083), Postdoctoral Interdisciplinary Innovation Startup Fund of Sichuan University (No. 10822041A2080). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013) and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Second University Hospital under No. 2022(047). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ferry JA, Scully RE. Mesonephric remnants, hyperplasia, and neoplasia in the uterine cervix. A study of 49 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1990;14:1100-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dierickx A, Göker M, Braems G, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix: Case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2016;17:7-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lang G, Dallenbach-Hellweg G. The histogenetic origin of cervical mesonephric hyperplasia and mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix studied with immunohistochemical methods. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1990;9:145-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bagué S, Rodríguez IM, Prat J. Malignant mesonephric tumors of the female genital tract: a clinicopathologic study of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:601-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valente PT, Susin M. Cervical adenocarcinoma arising in florid mesonephric hyperplasia: report of a case with immunocytochemical studies. Gynecol Oncol 1987;27:58-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silver SA, Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Mezzetti TP, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix: a study of 11 cases with immunohistochemical findings. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:379-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kondi-Pafitis A, Kairi E, Kontogianni KI, et al. Immunopathological study of mesonephric lesions of cervix uteri and vagina. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 2003;24:154-6. [PubMed]

- Angeles RM, August CZ, Weisenberg E. Pathologic quiz case: an incidentally detected mass of the uterine cervix. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004;128:1179-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukunaga M, Takahashi H, Yasuda M. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: a case report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Pathol Res Pract 2008;204:671-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anagnostopoulos A, Ruthven S, Kingston R. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix and literature review. BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012:bcr0120125632. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kenny SL, McBride HA, Jamison J, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix and corpus: HPV-negative neoplasms that are commonly PAX8, CA125, and HMGA2 positive and that may be immunoreactive with TTF1 and hepatocyte nuclear factor 1-β. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:799-807. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menon S, Kathuria K, Deodhar K, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma (endometrioid type) of endocervix with diffuse mesonephric hyperplasia involving cervical wall and myometrium: an unusual case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2013;56:51-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khalimbekova DI, Ul'rikh EA, Matsko DE, et al. Mesonephric (clear cell) cervical cancer. Vopr Onkol 2013;59:111-5. [PubMed]

- Tekin L, Yazici A, Akbaba E, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: A case report and review of the literature. J Pak Med Assoc 2015;65:1016-7. [PubMed]

- Kır G, Seneldir H, Kıran G. A case of mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix mimicking an endometrial clear cell carcinoma in the curettage specimen. J Obstet Gynaecol 2016;36:827-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ditto A, Martinelli F, Bogani G, et al. Bulky mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical surgery: report of the first case. Tumori 2016; [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puljiz M, Danolić D, Kostić L, et al. MESONEPHRIC ADENOCARCINOMA OF ENDOCERVIX WITH LOBULAR MESONEPHRIC HYPERPLASIA: CASE REPORT. Acta Clin Croat 2016;55:326-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cavalcanti MS, Schultheis AM, Ho C, et al. Mixed Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma and High-grade Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix: Case Description of a Previously Unreported Entity With Insights Into Its Molecular Pathogenesis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2017;36:76-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montalvo N, Redrobán L, Galarza D. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the cervix: a case report with a three-year follow-up, lung metastases, and next-generation sequencing analysis. Diagn Pathol 2019;14:71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Howitt BE, Nucci MR. Mesonephric proliferations of the female genital tract. Pathology 2018;50:141-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McFarland M, Quick CM, McCluggage WG. Hormone receptor-negative, thyroid transcription factor 1-positive uterine and ovarian adenocarcinomas: report of a series of mesonephric-like adenocarcinomas. Histopathology 2016;68:1013-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCluggage WG, Vosmikova H, Laco J. Ovarian Combined Low-grade Serous and Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinoma: Further Evidence for A Mullerian Origin of Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2020;39:84-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khalimbekova DI, Ul'rikh EA, Urmancheeva AF, et al. Clear cell (mesonephric) cancer: a rare tumor of the ovary with a mixed prognosis. Vopr Onkol 2014;60:379-83. [PubMed]

- Chapel DB, Joseph NM, Krausz T, et al. An Ovarian Adenocarcinoma With Combined Low-grade Serous and Mesonephric Morphologies Suggests a Müllerian Origin for Some Mesonephric Carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2018;37:448-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McNall RY, Nowicki PD, Miller B, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the cervix and vagina in pediatric patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004;43:289-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Erşahin C, Huang M, Potkul RK, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the vagina with a 3-year follow-up. Gynecol Oncol 2005;99:757-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bifulco G, Mandato VD, Mignogna C, et al. A case of mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the vagina with a 1-year follow-up. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2008;18:1127-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amal B. A tumor of the vagina not to overlook, the mesonephric adenocarcinoma: about a case report and review of literature. Pan Afr Med J 2015;21:126. [PubMed]

- Shoeir S, Balachandran AA, Wang J, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the vagina masquerading as a suburethral cyst. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr2018224758. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferry JA, Scully RE. Carcinoma in mesonephric remnants. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:1218-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto Y, Akagi A, Izumi K, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the uterine body of mesonephric origin. Pathol Int 1995;45:303-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ordi J, Nogales FF, Palacin A, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: CD10 expression as evidence of mesonephric differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:1540-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montagut C, Mármol M, Rey V, et al. Activity of chemotherapy with carboplatin plus paclitaxel in a recurrent mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus. Gynecol Oncol 2003;90:458-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marquette A, Moerman P, Vergote I, et al. Second case of uterine mesonephric adenocarcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:1450-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wani Y, Notohara K, Tsukayama C. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2008;27:346-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu H, Zhang L, Cao W, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:7012-9. [PubMed]

- Kim SS, Nam JH, Kim GE, et al. Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Corpus: A Case Report and Diagnostic Pitfall. Int J Surg Pathol 2016;24:153-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ando H, Watanabe Y, Ogawa M, et al. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus with intracystic growth completely confined to the myometrium: a case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol 2017;12:63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Na K, Kim HS. Clinicopathologic and Molecular Characteristics of Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma Arising From the Uterine Body. Am J Surg Pathol 2019;43:12-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yano M, Shintani D, Katoh T, et al. Coexistence of endometrial mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma and endometrioid carcinoma suggests a Müllerian duct lineage: a case report. Diagn Pathol 2019;14:54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel V, Kipp B, Schoolmeester JK. Corded and hyalinized mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus: report of a case mimicking endometrioid carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2019;86:243-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Cai Z, Ambelil M, et al. Mesonephric Adenocarcinoma of the Uterine Corpus: Report of 2 Cases and Review of the Literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2019;38:224-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horn LC, Höhn AK, Krücken I, et al. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinomas of the uterine corpus: report of a case series and review of the literature indicating poor prognosis for this subtype of endometrial adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2020;146:971-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kolin DL, Costigan DC, Dong F, et al. A Combined Morphologic and Molecular Approach to Retrospectively Identify KRAS-Mutated Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinomas of the Endometrium. Am J Surg Pathol 2019;43:389-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pors J, Cheng A, Leo JM, et al. A Comparison of GATA3, TTF1, CD10, and Calretinin in Identifying Mesonephric and Mesonephric-like Carcinomas of the Gynecologic Tract. Am J Surg Pathol 2018;42:1596-606. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mirkovic J, McFarland M, Garcia E, et al. Targeted Genomic Profiling Reveals Recurrent KRAS Mutations in Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinomas of the Female Genital Tract. Am J Surg Pathol 2018;42:227-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goyal A, Yang B. Differential patterns of PAX8, p16, and ER immunostains in mesonephric lesions and adenocarcinomas of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2014;33:613-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCluggage WG, Oliva E, Herrington CS, et al. CD10 and calretinin staining of endocervical glandular lesions, endocervical stroma and endometrioid adenocarcinomas of the uterine corpus: CD10 positivity is characteristic of, but not specific for, mesonephric lesions and is not specific for endometrial stroma. Histopathology 2003;43:144-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- d'Amati A, Pezzuto F, Serio G, et al. Mesonephric-Like Carcinosarcoma of the Ovary Associated with Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma: A Case Report. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:827. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Hu Q, Xu Q, Deng C, Guo T, Wu X. Mesonephric adenocarcinoma arising from the uterine corpus: case reports and literature review. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2023;6:30.