Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: report of 13 cases

Introduction

The wall of blood vessels comprises 3 layers: the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia. A pseudoaneurysm (PSA) is a hematoma that communicates with the lumen of a perforated artery, where the leaking blood is collected in the surrounding fibrous tissue. It is caused by a deficiency in one or more layers of the arterial wall. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm (UAP) is a PSA occurring in the uterine artery (1,2). The incidence of UAP remains unclear in China, although it has been reported to be 0.3% in other countries (3). UAP detected after laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy has also been reported (4), suggesting UAP may be more common than previously considered. Previously, UAP has been described in the literature as a rare complication, leading to postpartum hemorrhage “after traumatic delivery or traumatic pregnancy termination”. However, recent studies have revealed that nearly half of UAP cases occur after nontraumatic delivery (5). Here, we retrospectively analyzed the data of 13 UAP women admitted to our hospital from 2009 to 2018 and reviewed the relevant literature, with an attempt to further improve our understanding of UAP.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://gpm.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/gpm-20-74/rc).

Methods

UAP patients who were treated in our hospital from 2009 to 2018 were enrolled. The diagnostic criteria included the following: (I) with typical clinical symptoms such as repeated and sudden heavy vaginal bleeding or irregular vaginal bleeding; (II) a diagnosis of UAP made by digital subtraction angiography (DSA), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or postoperative pathology; and (III) with accompanying vascular malformations, such as arteriovenous fistula. Among these, a diagnosis of UAP (criterion II) was required. The clinical data, including medical histories, diagnosis and treatment methods, and outcomes, were retrospectively analyzed. The manifestations, treatments and outcomes were summarized using descriptive statistics. Quantitative variables were compared using Student’s t-test.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS statistics 17.0. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University (Registration No. 2021087). Individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Results

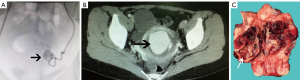

A total of 13 patients with UAP, aged 19–43 years, were included. The diagnosis was confirmed by DSA in 8 cases, by CT in 1 case, by MRI in 1 case, and by postoperative pathology in 3 cases (Figure 1). Among the 8 UAP cases confirmed by DSA, 3 had simple UAP and 5 had UAP accompanied by arteriovenous fistula; 9 patients had experienced significant traumatic event preceding onset of symptoms, while 4 had not. Among the 4 patients with nontraumatic event, 3 had a history of cesarean section or abortion and the 1 developed UAP after spontaneous delivery without any history of intrauterine manipulation. Vaginal bleeding was the main symptom in 12 of 13 patients; there was no vaginal bleeding in the remaining patient, in whom only a space-occupying lesion was found in the uterus. The treatment options included bilateral uterine artery embolization (UAE) (n=5), UAE followed by evacuation of the uterus (n=2), hysteroscopic lesion removal after UAE (n=1), laparoscopic lesion removal (n=1), and transabdominal or laparoscopic total/subtotal hysterectomy (n=3). The outcomes were good and without recurrence in 12 patients. Among them, 1 patient delivered a living infant by cesarean section 6 years after due to premature rupture of membranes at 32 weeks of gestation. The 13th patient had recurrent vaginal bleeding even after interventional embolization at another hospital. As the patient was young and had the desire to have children, she visited several hospitals and underwent a variety of treatments including balloon compression, medications, and placement of Mirena, but the results were poor (Table 1).

Table 1

| Case | Age (years) | Gravida and parity | Childbearing history | Clinical symptoms | Diagnostic evidence of UAP | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | G8P2+6 | Ectopic pregnancy: 1; cesarean section: 1; induced abortions: 5; medication abortion: 1 | Persistent vaginal bleeding and myometrial space-occupying lesion after medication abortion and uterine artery embolization | Contrast-enhanced pelvic CT | Total abdominal hysterectomy |

| 2 | 31 | G5P1+4 | Cesarean section: 1; induced abortions: 4 | A space-occupying lesion was found in the uterus 4 years prior, with no vaginal bleeding | Postoperative pathology | Laparoscopic lesion resection |

| 3 | 43 | G6P2+4 | Vaginal deliveries: 2; induced abortions: 4 | Intermittent vaginal bleeding for 11 days | Postoperative pathology | Total laparoscopic hysterectomy |

| 4 | 29 | G1P1 | Vaginal delivery: 1 | Recurrent heavy vaginal bleeding 1 month after normal delivery | DSA | Uterine artery embolization |

| 5 | 32 | G1P1 | Cesarean section: 1 | Recurrent vaginal bleeding 4 months after cesarean section | DSA | Uterine artery embolization |

| 6 | 24 | G3P1+2 | Cesarean section: 1; induced abortions: 2 | Vaginal bleeding 3 months after last induced abortion | DSA | Uterine artery embolization |

| 7 | 19 | G3P2+1 | Vaginal deliveries: 2; induced abortion: 1 | Evacuation of uterus was performed for vaginal bleeding 21 days after normal delivery; sudden heavy vaginal bleeding 6 days after the evacuation | DSA | Uterine artery embolization |

| 8 | 33 | G2P1+1 | Cesarean section: 1; induced abortion: 1 | Recurrent vaginal bleeding for 15 days 5 months after the last induced abortion | DSA | Uterine artery embolization |

| 9 | 27 | G5P1+4 | Cesarean section: 1; induced abortion: 4 | Irregular vaginal bleeding after the last induced abortion | DSA | Uterine artery embolization |

| 10 | 38 | G5P1+4 | Cesarean section: 1; induced abortion: 4 | Vaginal bleeding 5 days after the last induced abortion; uterine space-occupying lesion | DSA | Uterine artery embolization + evacuation of uterus |

| 11 | 25 | G4P2+2 | Cesarean section: 1; vaginal delivery: 1; induced abortions: 2 | Failed medication abortion for suspected cesarean scar pregnancy; uterine artery embolization + evacuation of the uterus; vaginal bleeding | Postoperative pathology | Subtotal abdominal hysterectomy |

| 12 | 35 | G4P1+3 | Vaginal delivery: 1; spontaneous abortions: 3 | Evacuation of the uterus performed 23 days after normal delivery; vaginal bleeding 8 days after the evacuation | DSA | Uterine artery embolization + hysteroscopic lesion removal |

| 13 | 25 | G2P0+2 | Induced abortions: 2 | Recurrent vaginal bleeding after last induced abortion | MRI | Uterine artery embolization + balloon compression + placement of Mirena ring + medications |

CT, computed tomography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Discussion

UAP usually occurs after traumatic delivery or traumatic pregnancy termination procedures, which include cesarean section, manual extraction of placenta, forceps delivery, vacuum extraction, induced abortion, and evacuation of the uterus (2). Among the 13 UAP patients enrolled in our current analysis, however, 4 (30.7%) had not undergone any traumatic intrauterine manipulation before the onset of the disease, and 1 (7.7%) did not even have a history of traumatic delivery. Baba et al. (3) analyzed 50 patients with UAP and also found 40% of the patients had not undergone any traumatic intrauterine manipulation before the onset of the disease and 24% had no history of traumatic delivery. Therefore, UAP can occur not only after traumatic uterine manipulation but also after nontraumatic pregnancy termination, like spontaneous abortion, drug induction or even natural vaginal delivery. The specific mechanism for this remains unclear, but it may be caused by bleeding following spontaneous uterine artery rupture during placental abruption or endometrial detachment.

The most common clinical manifestation of UAP is abnormal vaginal bleeding, and 92.3% (12/13) of our patients presented with varying degrees of vaginal bleeding. The remaining patient, however, had a history of cesarean section; she was found to have a space-occupying lesion in the uterus by the ultrasound scan during the routine physical examination 5 years after the surgery. During the 4-year follow-up, her menstruation was normal, and there was no abnormal vaginal bleeding throughout the course of the disease. Kim et al. (6) reported a case of UAP arising from the right uterine artery presenting with vaginal bleeding 2 years after termination of pregnancy, which was successfully treated by embolization. Thus, UAP does not necessarily cause bleeding immediately after its occurrence, and in some cases it may remain uneventful for a long period of time, which can be easily overlooked or misdiagnosed in clinical practice.

UAE is currently recognized as the first-line treatment option for UAP. UAE is an interventional radiological technique. After percutaneous femoral artery puncture, an arterial catheter is inserted directly into the uterine artery for injecting a permanent embolic particle to block the blood supply to the uterine artery, thus preventing further rupture and bleeding of the PSA (Figure 2). However, UAE is not always a preferred treatment in all UAP patients. In addition to socioeconomic reasons, such as the high cost of UAE, and the different fertility desires of individual patients, other medical factors should also be considered. First, it has been found that some asymptomatic and small-sized UAPs can resolve spontaneously (7), and use of UAE in these cases is undoubtedly a waste of medical resources. Second, interventional embolization has its inherent risks, and an increasing number of complications after UAE have been reported in recent years, which requires further investigations concerning its indications and contraindications.

One of our patients developed UAP after medication abortion; she had undergone UAE in another hospital but the treatment was ineffective, and finally she underwent hysterectomy in our hospital. Another UAP patient suffered from recurrent vaginal bleeding after UAE at another hospital, but responded poorly to various conservative treatments. As shown in the current retrospective analysis, 5 (62.5%) of the 8 patients with UAP confirmed by DSA had uterine arteriovenous fistulas. We therefore speculate that the coexistence of other uterine vascular malformations may be an important reason for the failure of UAE for UAP.

Lesion excision or (sub)total hysterectomy may be a more feasible option for patients who fail UAE or do not have sufficient embolization time for acute hemorrhage. Ota et al. (8) successfully treated a UAP patient with laparoscopic temporary clamping of the bilateral uterine arteries, which was followed by hysteroscopic surgery. This technique reduced intraoperative bleeding and preserved reproductive function and involved none of the risk of complications associated with UAE. It may also be a useful option in clinical settings.

In conclusion, UAP is not a rare disease, as it can occur after either traumatic intrauterine manipulation or nontraumatic pregnancy termination. Although the vast majority of UAP patients present with abnormal vaginal bleeding, a small proportion of UAP cases can be asymptomatic. In some cases, UAP may even resolve spontaneously without treatment or intervention. Careful identification, close follow-up, and prompt management are required for UAP patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://gpm.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/gpm-20-74/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://gpm.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/gpm-20-74/dss

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gpm.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/gpm-20-74/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University (Registration No. 2021087). Individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ouyang ZB, Xu YJ. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm. Progress in Obstetrics and Gynecology 2012;21:145-7.

- Baba Y, Matsubara S, Kuwata T, et al. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: not a rare condition occurring after non-traumatic delivery or non-traumatic abortion. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014;290:435-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baba Y, Takahashi H, Ohkuchi A, et al. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: its occurrence after non-traumatic events, and possibility of "without embolization" strategy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;205:72-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takeda A, Koike W, Imoto S, et al. Conservative management of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm after laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy and subsequent pregnancy outcome: case series and review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;182:146-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jennings L, Presley B, Krywko D. Uterine Artery Pseudoaneurysm: A Life-Threatening Cause of Vaginal Bleeding in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med 2019;56:327-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YA, Han YH, Jun KC, et al. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm manifesting delayed postabortal bleeding. Fertil Steril 2008;90:849.e11-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yahyayev A, Guven K, Bulakci M, et al. Spontaneous thrombosis of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: follow-up with Doppler ultrasonography and interventional management. J Clin Ultrasound 2011;39:408-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ota H, Fukushi Y, Wada S, et al. Successful treatment of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm with laparoscopic temporary clamping of bilateral uterine arteries, followed by hysteroscopic surgery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2017;43:1356-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Mei L, Pan X. Uterine artery pseudoaneurysm: report of 13 cases. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2021;4:23.