卵巢浆液性癌和腹膜浆液性癌的新辅助化疗、腹腔热灌注化疗和维持治疗现状

引 言

上皮性卵巢癌(EOC)是女性癌症死亡的第五大原因。大多数患者在确诊时为晚期,约80%复发,估计中位无进展生存期(PFS)约为12-18个月[1]。传统上,高级别浆液性EOC采用根治性手术加辅助化疗(ACT)。对于晚期卵巢癌,如果初次减瘤术有禁忌证,或完全细胞减灭术不可行的情况下,在间歇性肿瘤细胞减灭术(IDS)前进行新辅助化疗(NACT)是一种可行的治疗方法[2,3]。确定最佳选择患者的预测因素可能会提高无进展生存期(PFS)和总生存期(OS)。腹腔热灌注化疗(HIPEC)联合恶性肿瘤细胞减灭术(CRS)的疗效尚无共识。在新的靶向治疗的时代,HIPEC的应用有严格的标准。铂敏感复发性EOC的治疗通过加用以铂为基础的抗血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)抗体贝伐珠单抗或PARP抑制剂而得到改善。2016年,美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)批准贝伐珠单抗联合铂类化疗治疗铂敏感复发性EOC[4]。II-III期安慰剂对照试验评估了PARP抑制剂作为铂类药物治疗后的维持性治疗,在所有复发的EOC患者中,确实证明能延长PFS,这在具有种系或体细胞乳腺癌基因1和2(BRCA1/2)突变的人群中更为显著[5-9]。除了BRCA1/2突变细胞对PARP抑制剂高度敏感外,Fanconi贫血基因(BRIP1、PALB2)、核心RAD基因(RAD51C、RAD51D)以及直接参与同源重组修复(homologous recombination repair,HR)通路的基因(CHEK2、BARD1、NBN、ATM)或间接参与的基因(CDK12)的缺陷也增加了对PARP抑制剂的敏感性[10]。确定首次铂敏感复发后的最佳治疗方案,仍是一个未得到满足的需要。在这种情况下,需要设计直接比较两种可选维持治疗方案的试验。浆液性腹膜乳头状癌(SPPC)的临床表现、组织学特征和扩散方式与原发性EOC相似[11]。这些临床实体通常被视为一种单一的疾病,正确诊断可能是具有挑战性的。在被认为患有原发性EOC的患者中,15%的患者却是SPPC[11]。人们对EOC和SPPC的分子机制的差异进行了大量的研究,但在治疗方法上却大同小异。

新辅助化疗(NACT)vs 初次肿瘤细胞减灭术(UDS)

大多数新诊断的卵巢癌患者接受根治性手术治疗,然后辅以铂类化疗[12]。然而,手术治疗方案仍存在争议。对于晚期高级别浆液性EOC患者,在UDS方案和NACT+IDS方案之间的选择并不总是明确的。在这种情况下,有必要采用精确的患者选择标准来指导治疗决策。

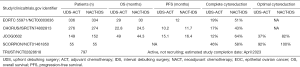

完全肿瘤细胞减灭是最重要的临床终点,与提高减灭术后患者的存活率有关[13]。最初,EORTC 55971试验将晚期/转移性EOC患者随机分为两组:UDS+ACT或NACT+IDS+ACT(NCT00003636)[2]。五年后发表了类似设计的CHORUS试验(ISRCTN74802813)[3]。这两项研究都是非劣研究,并证明了两个治疗组的OS相同。基于这两项研究,在晚期EOC患者中,NACT+IDS已被认为与UDS有相同疗效。在晚期EOC患者中比较UDS和IDS的III期随机临床试验总结在表1中。

Full table

在手术决策之前,应考虑几个预后因素[14,15]。间皮素、FLT4、α-1酸性糖蛋白(AGP)和肿瘤抗原125(Ca-125)被认为是将抗血管生成药物(贝伐珠单抗)纳入一线治疗的预测生物标志物[16]。血管生成和血管重塑是一个复杂的过程,涉及到细胞因子血管生成素-1(Ang1)和血管生成素2(Ang2)的调节。Ang1是一种强有力的血管生成生长因子,通过Tie2传递信号,而Ang2最初被认为是血管干扰剂,具有与VEGF不同的功能,并通过Tie2发挥拮抗作用。

基因组因素,如细胞周期素E1扩增和BRCA1/2突变丢失,也对决定IDS与UDS有预测价值,因为它们区分了化疗耐药和化疗敏感的高级别浆液性EOC[17]。Gorodnova等人报道,BRCA1/2胚系突变的EOC患者对铂类NACT表现出高度的敏感性[18]。同样,同源重组(HR)基因BRCA2、p53和FANCB的表达与NACT+IDS治疗后EOC患者的OS延长相关,并代表了铂类NACT的一类积极预测因素[19]。

肿瘤浸润淋巴细胞(TILs)和无肿瘤细胞DNA(CfDNA)也被认为是预测的生物标志物,但它们的应用有限,缺乏标准的分离方法[20]。高水平的TILs可能与对NACT反应好相关,提示宿主免疫反应影响肿瘤的化疗敏感性[21-23]。

对130例EOC患者的肿瘤组织进行回顾性分析,CD3(P=0.03)、PD-L1(P=0.007)和PD-1(P=0.02)高表达者OS延长[24]。CfDNA分析识别基因组改变并捕捉原发性和转移性肿瘤的异质性。CfDNA分析可以洞察分子特征、早期诊断、治疗反应和/或耐药性的监测,以及在辅助环境下患者治疗的最佳选择[25]。

采用评分系统评估患者的体重指数(BMI)、Ca-125水平和影像学分期,以预测UDS的潜在受益者。BMI<30 kg/m2,Ca-125<100IU/L,正电子发射断层扫描/计算机断层扫描(PET/CT)未提示膈、网膜癌病或实质转移的患者,UDS后达到完全细胞减灭的机会更大[26]。此外,65岁以上、白蛋白水平<25g/L和腹水>1L的患者不会从UDS中受益。

当然,广泛性癌症导致的不能切除的病变应该用NACT治疗[21]。从外科角度来看,小肠和大肠内的深层浸润或弥漫性转移与高发病率相关[16]。同样,腹腔淋巴结受累与大肠切除和小肠系膜转移的可能性增加相关[27]。在初次肿瘤细胞减灭术中,似乎淋巴结受累并不会促进初次肿瘤细胞减灭,而腹膜受累则会导致手术并发症[16,28,29]。Fagotti腹腔镜指数是根据细胞减灭术前腹腔镜检查确定的客观参数决定的百分制评分。预测参数包括腹膜外和转移性病变的因素,如腹膜癌、膈肌和肠系膜病变、网膜转移、肠胃浸润以及肝转移[30]。每个参数若存在则分别得2分,否则为0分。将患者分为不完全细胞减灭的三个风险组。高危人群将接受NACT治疗。对于中间型患者,腹腔镜检查用于评估病变可切除性是合理的。而低风险患者则可以接受初次肿瘤细胞减灭术。

对于高级别浆液性EOC的影像技术,PET/CT扫描被推荐用来评估病变的范围,并由此决定在晚期EOC中IDS或UDS的选择[21]。恶性胸腔积液、横膈上转移者完全细胞减灭的几率较低。然而,需要进一步的研究来阐明这些影像学特征的预测价值。此外,含有18F-FDG的PET被证明足以预估NACT效果[21]。建议对胸膜受累的患者进行胸腔镜检查,以达到分期的目的,而实时超声弹性成像目前在这方面作用有限[21]。弥散加权磁共振成像(DW-MRI)的预测价值是基于提供肠管浆膜、肠系膜血管和远处受累部位的信息[21,29]。

腹腔热灌注化疗(HIPEC)

尽管CRS和全身化疗仍然是EOC的标准治疗方法,HIPEC如今已经成为候选患者的一种选择[31]。HIPEC是在恶性肿瘤细胞减灭术之后,在加热灌流液中进行腹腔化疗。与静脉给药相比,腹腔化疗可降低血浆毒性,并通过加热提高疗效[32]。

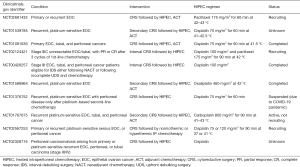

表2总结了几个不同情况下的II/III期随机试验。其中4个试验纳入初次治疗的患者,1个纳入初次肿瘤细胞减灭术患者,2例纳入间歇性肿瘤细胞减灭术患者(在3周期NACT治疗后)。最新的国家综合癌症网络(NCCN)指南支持间歇性肿瘤细胞减灭术进行HIPEC[33]。此外,4项临床试验招募了进行二次CRS的复发性患者。在这种情况下,HIPEC的使用似乎得到了更广泛的研究。对16项研究的分析得出结论,复发性EOC患者行HIPEC能提高生存率[34]。发病率一直在12%至30%之间。与治疗相关的副作用通常与骨髓抑制和肾毒性有关(35例)。然而,对手术和HIPEC的并发症进行区别是具有挑战性的[35]。OS和PFS率与OCEANS,DESKTOP,CAL YPSO 试验中报告的比率一致;然而,由于这些试验的单独设计,直接正面比较是不可行的[34,36-38]。

Full table

此外,还应解决药物的最佳选择、剂量、时间和温度等问题。目前,HIPEC在晚期EOC患者的多模式治疗中应用的理由很充分。对这种治疗性干预的实施持怀疑态度的主要原因与耐受性有关[39]。与单纯CRS相比,HIPEC死亡率和发病率的证据相当不确定、不一致[40,41]。HIPEC应该在组织良好的机构为合适的患者提供[42]。显然,有必要进一步进行设计良好的前瞻性随机试验,以阐明HIPEC在原发性EOC治疗中的作用。

维持性治疗

尽管最近在初次治疗方面取得了成就,但大约80%的EOC患者在首次诊断后5年内复发。复发性EOC的中位OS为12至24月[43]。直到最近,铂敏感复发性EOC患者接受以铂为基础的再挑战方案的治疗。在以铂为基础的方案中加入抗VEGF抗体贝伐珠单抗或PARP抑制剂,使这组患者的治疗结果得到了改善。

事实上,三个III期试验的结果显示,在铂类化疗中加入贝伐珠单抗,然后以贝伐珠单抗维持治疗,PFS比单独化疗延长[4,38,44]。这一治疗策略应该特别适用于复发时疾病负担高的患者,在这些患者中,迅速缩小肿瘤可能会导致更好地控制疾病相关症状。FDA和欧洲医学会(EMA)分别于2016年和2017年批准贝伐珠单抗+卡铂+吉西他滨/紫杉醇联合治疗铂敏感的复发性EOC。批准是基于OCEANS试验的结果,该试验结果显示,与单独化疗相比,联合用药组的客观应答率(ORR)提高了约20%[38]。尽管如此,来自ENGOTov18/AGO-OVAR2.21试验的最新证据显示,卡铂+聚乙二醇化阿霉素脂质体的疗效好于卡铂+吉西他滨+贝伐珠单抗[中位PFS 13.3 vs. 11.7月,危险比(HR):0.8;95%可信区间(CI):0.68-0.96,P=0.0128][45]。

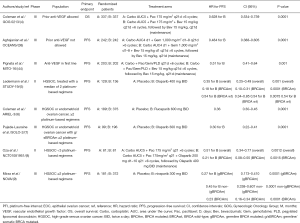

PARP抑制剂改变了铂敏感复发性EOC患者的治疗标准。奥拉帕利、卢卡帕利和尼拉帕利获得了FDA和/或EMA用于不同情况的EOC的批准。维拉帕利和他唑帕利处于较早的临床开发阶段[46,47]。已批准的PARP抑制剂已被评估为复发EOC患者的维持治疗用药。II-III期安慰剂对照试验显示能改善所有人群的PFS,特别是在那些BRCA1/2胚系或体系突变的人群中[5-9]。BRCA和HR缺陷状态都是预测化疗和PARP抑制剂效果的新的标志物。胚系BRCA1/2突变增加了EOC的风险,约占EOC的14%。这些基因编码的蛋白质在HR缺陷引起的双链DNA断裂(DSBs)的修复中起着至关重要的作用。此外,BRCA1/2的体系突变和表观遗传学失活也与散发性卵巢癌有关。除了BRCA1/2基因的胚系致病突变外,BRIP1、RAD51C、RAD51D和错配修复基因的突变也会增加EOC的风险[10]。此外,选择PARP抑制剂联合抑制HR缺陷的药物代表了一种新的治疗方法,可能通过先天性或获得性HR缺陷使EOC对PARP抑制剂敏感。进一步的研究应该有助于确定患者最有可能从联合治疗中受益[48]。

副作用是选择维持治疗的最佳药物的关键因素。贝伐珠单抗的副作用总体可控,具体毒性与其作用机制有关。最常见的不良事件包括高血压、蛋白尿、出血和血栓栓塞事件、伤口愈合不良和胃肠道穿孔。因此,贝伐珠单抗引起副作用的风险较高的患者应在有适应症的情况下使用PARP抑制剂进行治疗[49]。使用PARP抑制剂的维持治疗一般耐受性良好,这会影响患者的依从性和生活质量,这是维持治疗阶段非常重要的因素。这些药物最常见的严重毒性包括贫血和疲劳[50]。尽管PARP抑制剂总体上抑制PARP的催化活性,但根据每个单独分子的大小和结构,它们捕获PARP的能力存在显著差异。这解释了不同程度的细胞毒性及其不同的安全性[51]。

复发性EOC的治疗方法进一步受到一线治疗格局变化的影响。SOLO-1试验为BRCA1/2突变患者建立了一个新的治疗标准;与安慰剂相比,奥拉帕利组使疾病进展的风险降低了大约70%[1]。在复发高危人群中,尼拉帕利在初次治疗中也是有效的,PFS比安慰剂组延长。根据Myriad[9,52]的“myChoice HRD”商业基因组缺陷分析,BRCA1/2突变患者和HR缺陷评分阳性的BRCA野生型患者获得了好处。PAOLA1 GINECO/ENgOT-ov25试验也报告了类似的结果,评估了奥拉帕利与贝伐珠单抗的联合[53]。随着更多的患者以PARP抑制剂为一线治疗,建立最佳治疗序列的临床试验是有必要的。

表3总结了首次铂敏感复发后的维持治疗临床试验数据。由于缺乏面对面的研究,很难直接比较不同的PARP抑制剂和贝伐珠单抗的活性。

Full table

EOC免疫治疗的未来方向

尽管临床前研究的早期数据表明EOC具有免疫原性微环境,但免疫检查点抑制剂在临床试验中尚未产生良好的反应。根据生物标志物状态分析,PD-L1阳性不能预测纳武利尤单抗试验的客观应答,而在免疫细胞中≥5%PD-L1表达的8例患者中,有2例观察到对阿替唑珠单抗的客观应答[54,55]。在一项评估Avelumab疗效的研究中,当PD-L1阳性的截断值设置为1%[56]时,PD-L1阳性和阴性队列中的ORR分别为11.8%和7.9%。

Keynote-100试验是关于EOC中单一免疫检查点抑制剂的最大规模的研究。PD-L1表达以联合阳性评分(CPS)衡量,定义为PD-L1阳性细胞与存活肿瘤细胞的比值[57]。pembrolizumab对CPS<1、CPS≥1和CPS≥10的ORR值分别为5%、10.2%和17.1%。用抗细胞毒性T淋巴细胞相关蛋白4(CTLA-4)的单克隆抗体ipilimumab对9例晚期EOC患者用粒细胞巨噬细胞集落刺激因子免疫后,仅1例出现部分应答(PR)[58]。

在对40例复发的铂敏感卵巢癌患者进行的II期试验中,用抗CTLA-4抗体ipilimumab的单克隆治疗,ORR达到10.3% [59]。根据这些试验的结果,EOC似乎对抗PD-1/PD-L1或抗CTLA单一治疗反应不佳。然而,应该考虑到的是,入选的患者在此前接受了大量的化疗。此外,这些研究的样本大多很小。因此,应该谨慎地得出结论。

免疫治疗联合化疗是提高肿瘤免疫原性和治疗效果的合理策略。III期JAVELIN Ovarian 200试验纳入了566名铂类耐药或铂类难治性EOC患者,他们接受了最多3个系列的治疗[60]。在聚乙二醇化阿霉素脂质体中加入avelumab并不能显著延长PFS和OS。而PD-L1阳性亚组(≥肿瘤细胞的1%或≥免疫细胞的5%)患者的生存率明显提高(PFS:HR:0.72,P=0.11;OS:HR:0.59;P=0.005)。此外,联合应用VEGF阻断剂是提高免疫治疗抗肿瘤疗效的另一种潜在的方法。在不同的EOC研究中(NCT03038100、NCT02891824和NCT02839707)有随机III期试验正在对化疗和/或贝伐珠单抗的基础上加用atezolizumab进行研究[61-63]。总体而言,为选择免疫治疗的合适患者确定预测生物标志物是至关重要的。

浆液性原发性腹膜癌

SPPC具有与原发性EOC不同的微妙临床特征。SPPC影响超重和老年患者,以及那些产次较多和月经初潮较晚的患者。肿瘤多为多灶性,以弥漫性微结节播散为特征,导致上腹部和横隔面肿瘤负荷较高。此外,在患者体内的多个腹膜沉积中也观察到了不协调的等位基因丢失。不同的基因事件发生在不同的腹膜位点这一事实,利用单灶性将SPPC与EOC区别开来[64,65]。

在分子生物学方面,SPPC更常见的特征是免疫组化高表达人表皮生长因子受体2(HER2),增殖指数Ki-67高于EOC[66-68]。这为SPPC的间变性和铂抗药的发展提供了理论基础。雌激素和孕激素受体在SPPC中的表达频率较低,类似于染色体杂合性丢失的发生率较低[66,68]。最后,p53和BCL2的蛋白表达模式、微血管密度和microRNA图谱没有差别[66,67,69,70]。基于这一分子证据,SPPC和原发性EOC似乎代表了一个疾病系列的两个临床类型,而不是完全独立的两种恶性肿瘤。

SPPC患者的推荐诊断检查包括基本的血液分析和胸部、腹部、骨盆扫描的成像[71]。血清Ca-125不是病原学的,但如果基线水平升高,则可以进行监测[72]。总体而言,手术分期仍然是诊断的金标准,而上、下消化道系统的内窥镜检查和PET-CT扫描可以提供额外的信息[73]。

组织学上,SPPC表现为复杂的乳头状或腺状结构,类似于乳头状浆液性EOC[74]。典型的免疫组化表现为CK7、CD15、S-100、p53、WT-1、ER和PAX-8阳性,calretinin阴性[75-77]。SPPC应与腹膜间皮瘤鉴别,后者Ber-EP4和MOC-31阴性,calretinin和D2-40阳性[78]。

SPPC通常转移到腹腔、盆腔和主动脉旁淋巴结,这突出了积极的局部控制的重要性[79]。全腹膜切除术的基本原理是去除前驱部位和微小残留病变[80]。据报道,60%的外观正常的腹膜有残留肿瘤[81,82]。一般来说,淋巴结在SPPC和EOC中的受累程度相同。强烈建议SPPC患者进行系统性淋巴结清扫是因为与EOC相比,术后发生粘连的频率更高,从而限制了复发后进一步手术[80,83]。NACT对于实现最优局部控制是有效的[84]。对NACT完全应答(CR)的患者可能不需要手术。根据一篇多病例报道,在44例接受NACT治疗的SPPC患者中,只有17例进行了CRS[85]。然而,手术亚组复发率较低(65% vs. 93%),中位PFS(25月 vs. 9月;P=0.001)和OS(48月 vs. 18月;P=0.0016)明显延长[85]。

CRS-HIPEC对原发或复发SPPC患者的治疗策略仍在研究中。将HIPEC加入到标准的多模式治疗中,可以局部控制腹膜癌[86]。在两组接受CRS+HIPEC治疗的32例和22例患者中,5年OS分别为57.4%和64.9%[80,87]。在化疗方面,铂类/紫杉烷联合化疗的ORR为53~100%,中位OS为15~42个月(88个月)。除了EOC患者,PARP抑制剂和贝伐珠单抗的临床试验无论是在初次治疗还是在维持治疗阶段,都会招募SPPC患者;然而,研究并没有分别提供每种疾病的结果[46,48]。

总 结

对于UDS和IDS的最佳手术时机和患者选择标准,目前缺乏共识。应根据循证预后因素进行决策。完全肿瘤细胞减灭仍然是最可靠的临床终点,获得更长的生存期。在EOC治疗中实施HIPEC也有很强的理论基础,相关的随机临床试验正在进行中。EOC维持治疗的格局正在迅速变化。目前,抗血管生成药物(贝伐珠单抗)和PARP抑制剂(奥拉帕利、卢卡帕利和尼拉帕利)已被纳入维持治疗,并使铂敏感的复发性EOC患者的PFS延长。然而,在缺乏直接临床试验数据的情况下,关于选择最佳制剂的问题仍然存在。传统上,SPPC患者的治疗方式与晚期/转移性原发性EOC患者相似。由于缺乏前瞻性试验,支持证据仅限于单个机构的回顾性系列研究。

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from the Research and Innovation department of Medway NHS Foundation Trust.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gpm.amegroups.org/article/view/10.21037/gpm-20-41/coif). SB serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Gynecology and Pelvic Medicine from May 2020 to Apr 2022. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Boussios S, Moschetta M, Karihtala P, et al. Development of new poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in ovarian cancer: Quo Vadis? Ann Transl Med 2020; [Crossref]

- Vergote I, Tropé CG, Amant F, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:943-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2015;386:249-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coleman RL, Brady MF, Herzog TJ, et al. Bevacizumab and paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy and secondary cytoreduction in recurrent, platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study GOG-0213): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:779-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1382-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso DARIEL3 investigators, et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;390:1949-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle FSOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21 investigators, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1274-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oza AM, Cibula D, Benzaquen AO, et al. Olaparib combined with chemotherapy for recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:87-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt JENGOT-OV16/NOVA investigators, et al. niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2154-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Karathanasi A, Cooke D, et al. PARP Inhibitors in ovarian cancer: the route to "Ithaca". Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9:55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Serous papillary peritoneal carcinoma: unknown primary tumour, ovarian cancer counterpart or a distinct entity? A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010;75:27-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lheureux S, Braunstein M, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer: evolution of management in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69:280-304. [PubMed]

- du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials: by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d'Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l'Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer 2009;115:1234-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clifford C, Vitkin N, Nersesian S, et al. Multi-omics in high-grade serous ovarian cancer: biomarkers from genome to the immunome. Am J Reprod Immunol 2018;80:e12975. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Zyl B, Tang D, Bowden NA. Biomarkers of platinum resistance in ovarian cancer: what can we use to improve treatment. Endocr Relat Cancer 2018;25:R303-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colombo N, Sessa C, du Bois A, et al. ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease†. Ann Oncol 2019;30:672-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katchman BA, Chowell D, Wallstrom G, et al. Autoantibody biomarkers for the detection of serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2017;146:129-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gorodnova TV, Sokolenko AP, Ivantsov AO, et al. High response rates to neoadjuvant platinum-based therapy in ovarian cancer patients carrying germ-line BRCA mutation. Cancer Lett 2015;369:363-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kessous R, Octeau D, Klein K, et al. Distinct homologous recombination gene expression profiles after neoadjuvant chemotherapy associated with clinical outcome in patients with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2018;148:553-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katopodis P, Chudasama D, Wander G, et al. Kinase Inhibitors and Ovarian Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1357. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho JH, Kim S, Song YS. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced ovarian cancer: optimal patient selection and response evaluation. Chin Clin Oncol 2018;7:58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Josahkian JA, Saggioro FP, Vidotto T, et al. Increased STAT1 expression in high grade serous ovarian cancer is associated with a better outcome. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2018;28:459-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jin C, Xue Y, Li Y, et al. A 2-protein signature predicting clinical outcome in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2018;28:51-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martin de la Fuente L, Westbom-Fremer S, Arildsen NS, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostically favorable in advanced high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Virchows Arch 2020;477:83-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliveira KCS, Ramos IB, Silva JMC, et al. Current perspectives on circulating tumor DNA, precision medicine, and personalized clinical management of cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2020;18:517-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chesnais M, Lecuru F, Mimouni M, et al. A pre-operative predictive score to evaluate the feasibility of complete cytoreductive surgery in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. PLoS One 2017;12:e0187245. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Angeles MA, Ferron G, Cabarrou B, et al. Prognostic impact of celiac lymph node involvement in patients after frontline treatment for advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:1410-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powless CA, Aletti GD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, et al. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in apparent early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: implications for surgical staging. Gynecol Oncol 2011;122:536-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McIntosh LJ, O'Neill AC, Bhanusupriya S, et al. Prognostic significance of supradiaphragmatic lymph nodes at initial presentation in patients with stage III high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;42:2513-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Makar AP, Tropé CG, Tummers P, et al. Advanced ovarian cancer: primary or interval debulking? five categories of patients in view of the results of randomized trials and tumor biology: primary debulking surgery and interval debulking surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Oncologist 2016;21:745-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rufián S, Muñoz-Casares FC, Briceño J, et al. Radical surgery-peritonectomy and intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in recurrent or primary ovarian cancer. J Surg Oncol 2006;94:316-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker PH. Surgical responsibilities in the management of peritoneal carcinomatosis. J Surg Oncol 2010;101:713-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: ovarian cancer, version 1.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17:896-909. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hotouras A, Desai D, Bhan C, et al. Heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for patients with recurrent ovarian cancer: a systematic literature review. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016;26:661-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polom K, Roviello G, Generali D, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for treatment of ovarian cancer. Int J Hyperthermia 2016;32:298-310. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wagner U, Marth C, Largillier R, et al. Final overall survival results of phase III GCIG CALYPSO trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and carboplatin vs paclitaxel and carboplatin in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2012;107:588-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harter P, du Bois A, Hahmann M, et al. Surgery in recurrent ovarian cancer: the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie (AGO) DESKTOP OVAR trial. Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:1702-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aghajanian C, Blank SV, Goff BA, et al. OCEANS: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent epithelial ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2039-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quenet F, Elias D, Roca L, et al. A UNICANCER phase III trial of hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC): PRODIGE 7. J Clin Oncol 2018;36: abstr LBA3503.

- Cascales Campos PA, Gil J, Munoz-Ramon P, et al. Hipec in ovarian cancer. Why is it still the ugly duckling of intraperitoneal therapy? J Cancer Sci Ther 2016;8:30.

- Fotopoulou C, Sehouli J, Mahner S, et al. HIPEC: HOPE or HYPE in the fight against advanced ovarian cancer? Ann Oncol 2018;29:1610-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Riggs MJ, Pandalai PK, Kim J, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10:43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ledermann JA, Raja FA, Fotopoulou C, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2018;29:iv259. [Crossref]

- Pignata S, Lorusso D, Joly F, et al. Chemotherapy plus or minus bevacizumab for platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients recurring after a bevacizumab containing first line treatment: the randomized phase 3 trial: MITO16B-MaNGO OV2B-ENGOT OV17. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:5506. [Crossref]

- Pfisterer J, Shannon CM, Baumann K, et al. AGO-OVAR 2.21/ENGOT-ov 18 Investigators. Bevacizumab and platinum-based combinations for recurrent ovarian cancer: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:699-709. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Karihtala P, Moschetta M, et al. Veliparib in ovarian cancer: a new synthetically lethal therapeutic approach. Invest New Drugs 2020;38:181-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Abson C, Moschetta M, et al. Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors: Talazoparib in Ovarian Cancer and Beyond. Drugs R D 2020;20:55-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Karihtala P, Moschetta M, et al. Combined Strategies with poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for the treatment of ovarian cancer: a literature review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9:87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lorusso D, Fontanella C, Maltese G, et al. The safety of antiangiogenic agents and PARP inhibitors in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2017;16:687-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mullen MM, Kuroki LM, Thaker PH. Novel treatment options in platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: a review. Gynecol Oncol 2019;152:416-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2495-505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- González-Martín A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2391-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S, et al. Olaparib plus bevacizumab as first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2416-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Ikeda T, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of anti-PD-1 antibody, nivolumab, in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:4015-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu JF, Gordon M, Veneris J, et al. Safety, clinical activity and biomarker assessments of atezolizumab from a phase I study in advanced/recurrent ovarian and uterine cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2019;154:314-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Disis ML, Taylor MH, Kelly K, et al. Efficacy and safety of avelumab for patients with recurrent or refractory ovarian cancer: phase 1b results from the JAVELIN solid tumor trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:393-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matulonis UA, Shapira-Frommer R, Santin AD, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced recurrent ovarian cancer: results from the Phase 2 KEYNOTE-100 study. Ann Oncol 2019;30:1080-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hodi FS, Butler M, Oble DA, et al. Immunologic and clinical effects of antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 in previously vaccinated cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:3005-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phase II study of ipilimumab monotherapy in recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01611558 (Accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Fujiwarab K, Ledermann JA, et al. Avelumab alone or in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin alone in platinum-resistant or refractory epithelial ovarian cancer: Primary and biomarker analysis of the phase III JAVELIN Ovarian 200 trial. Gynecol Oncol 2019;154:21-2. [Crossref]

- A study of atezolizumab versus placebo in combination with paclitaxel, carboplatin, and bevacizumab in participants with newly-diagnosed stage III or stage IV ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (IMagyn050). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03038100 (Accessed on 11 June 2020).

- ATALANTE: atezolizumab vs placebo phase III study in late relapse ovarian cancer treated with chemotherapy + bevacizumab (ATALANTE). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02891824 (Accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride with atezolizumab and/or bevacizumab in treating patients with recurrent ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02839707 (Accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Huang LW, Garrett AP, Muto MG, et al. Identification of a novel 9 cM deletion unit on chromosome 6q23-24 in papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Hum Pathol 2000;31:367-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schorge JO, Muto MG, Welch WR, et al. Molecular evidence for multifocal papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum in patients with germline BRCA1 mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:841-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halperin R, Zehavi S, Hadas E, et al. Immunohistochemical comparison of primary peritoneal and primary ovarian serous papillary carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2001;20:341-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen LM, Yamada SD, Fu YS, et al. Molecular similarities between primary peritoneal and primary ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2003;13:749-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang LW, Garrett AP, Schorge JO, et al. Distinct allelic loss patterns in papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum. Am J Clin Pathol 2000;114:93-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terai Y, Ueda M, Kumagai K, et al. Tumor angiogenesis and thymidine phosphorylase expression in ovarian carcinomas including serous surface papillary adenocarcinoma of the peritoneum. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2000;19:354-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pentheroudakis G, Spector Y, Krikelis D, et al. Global microRNA profiling in favorable prognosis subgroups of cancer of unknown primary (CUP) demonstrates no significant expression differences with metastases of matched known primary tumors. Clin Exp Metastasis 2013;30:431-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fizazi K, Greco FA, Pavlidis N, et al. Cancers of unknown primary site: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2015;26:v133-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iavazzo C, Vorgias G, Katsoulis M, et al. Primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: clinical and laboratory characteristics. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008;278:53-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prat JFIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2014;124:1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibbs AR. Tumours of the serosal membranes. armed forces institute of pathology atlas of tumour pathology, fourth series, fascicle 3. Occup Environ Med 2007;64:288. [Crossref]

- Liu Q, Lin JX, Shi QL, et al. Primary peritoneal serous papillary carcinoma: a clinical and pathological study. Pathol Oncol Res 2011;17:713-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ozcan A, Shen SS, Hamilton C, et al. PAX 8 expression in non-neoplastic tissues, primary tumors, and metastatic tumors: a comprehensive immunohistochemical study. Mod Pathol 2011;24:751-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuo K, Sheridan TB, Mabuchi S, et al. Estrogen receptor expression and increased risk of lymphovascular space invasion in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2014;133:473-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boussios S, Moschetta M, Karathanasi A, et al. Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: clinical aspects, and therapeutic perspectives. Ann Gastroenterol 2018;31:659-69. [PubMed]

- Steinhagen PR, Sehouli J. The involvement of retroperitoneal lymph nodes in primary serous-papillary peritoneal carcinoma. a systematic review of the literature. Anticancer Res 2011;31:1387-94. [PubMed]

- Deraco M, Sinukumar S, Salcedo-Hernández RA, et al. Clinico-pathological outcomes after total parietal peritonectomy, cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in advanced serous papillary peritoneal carcinoma submitted to neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy- largest single institute experience. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:2103-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Unal OU, Oztop I, Yazici O, et al. Treatment and prognostic factors in primary peritoneal carcinoma: a multicenter study of the Anatolian Society of Medical Oncology (ASMO). Oncol Res Treat 2014;37:332-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crane EK, Sun CC, Ramirez PT, et al. The role of secondary cytoreduction in low-grade serous ovarian cancer or peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2015;136:25-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Atallah D, Rassy EE, Chahine G. Is the LION strong enough? Future Oncol 2017;13:1835-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luyckx M, Leblanc E, Filleron T, et al. Maximal cytoreduction in patients with FIGO stage IIIC to stage IV ovarian, fallopian, and peritoneal cancer in day-to-day practice: a Retrospective French Multicentric Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2012;22:1337-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connolly CF, Yahya S, Chan KK, et al. Outcomes following interval debulking surgery in primary peritoneal carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2016;36:255-9. [PubMed]

- Yuan J, He L, Han B, et al. Long-term survival of high-grade primary peritoneal papillary serous adenocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol 2017;15:76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakrin N, Gilly FN, Baratti D, et al. Primary peritoneal serous carcinoma treated by cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. A multi-institutional study of 36 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 2013;39:742-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet 2012;379:1428-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Boussios S, Sadauskaite A, Kanellos FS, Tsiouris AK, Karathanasi A, Sheriff M. A narrative review of neoadjuvant, HIPEC and maintenance treatment in ovarian and peritoneal serous cancer: current status. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2020;3:19.