Treatment of cervical squamous cell carcinoma with transabdominal lymph node resection and QM-C2 surgery: a surgical technique

Highlight box

Surgical highlights

• Using paracervical space anatomy techniques, the surgery is standardized by locating key anatomical landmarks and membrane spaces, fully exposing important structures such as blood vessels, nerves, and ligaments in the paracervical area. Energy devices, such as ultrasonic scalpels, are used to sharply dissect lymph nodes along anatomical spaces while simultaneously sealing small blood vessels and lymphatics, which increases surgical safety and reduces intraoperative and postoperative complications.

What is conventional and what is novel/modified?

• Traditional open surgery for cervical cancer encompasses a wide range and fails to clearly expose structures such as paracervical blood vessels, ligaments, and nerves. The extent of paracervical resection often does not meet standardized criteria. During surgery, “tearing” blunt dissection techniques are frequently used to remove lymph nodes and separate tissues, leading to increased intraoperative bleeding and postoperative complications such as lymphatic leakage. The space around the cervix is delineated by identifying and isolating key anatomical landmarks as well as dissecting and separating fascial planes, which facilitates the exposure of vital structures. The extent of the procedure is standardised by the management of the tissues surrounding the cervix and uterine ligaments, and stripping the membranous fissure is a quick and safe way to achieve these goals.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• In open surgery, precise separation of the paracervical spaces and layer-by-layer anatomical dissection establish a standardized surgical procedure, achieving better surgical outcomes.

Introduction

Cervical cancer has the highest incidence and mortality rates among the three major gynecological malignancies. According to data released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO) (1), there are approximately 661,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 348,000 deaths worldwide in 2022. In China alone, there were about 151,000 new cases and 56,000 deaths (2). Accordingly, the WHO has launched a global strategy to eliminate cervical cancer (3), declaring that 194 countries aim to achieve the “90-70-90” targets by 2030, which embody improving vaccination coverage, promoting standardized cervical cancer screening, and enhancing the level of standardized diagnosis and treatment for cervical cancer patients. This includes the homogenization and standardization of surgical treatment for early-stage cervical cancer (4).

The QM classification employs international anatomical terms to delineate the three-dimensional structure of the extent of hysterectomy, thereby establishing a contemporary surgical classification system (5). The extensive hysterectomy of QM-C2 type is the foundation of all QM classifications (6). Lymph node metastasis is an important independent risk factor affecting the prognosis of cervical cancer (7). The basic criteria for successful malignant tumor surgery are: (I) complete removal of the lesion with a sufficient margin of normal tissue around it; (II) complete removal of the lymph nodes in the corresponding region. In addition to pelvic lymphadenectomy, the NCCN guidelines post-2009 indicate (8) the need for para-aortic lymphadenectomy under the following conditions: Patients with cervical cancer stages IB2-IIA2 (locally advanced); Suspected or confirmed pelvic and para-aortic lymph node enlargement preoperatively or intraoperatively, suggesting possible metastasis; Pathological types such as small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or other special types.

In 2020−2021, the NCCN guidelines (9) clearly stated that open extensive hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy ± para-aortic lymphadenectomy was the standard surgical procedure for cervical cancer at corresponding stages. This surgery is extensive and often accompanied by various intraoperative and postoperative complications. By employing precise paracervical space anatomy, the standardization of open extensive hysterectomy for cervical cancer can be achieved, reducing complications while also decreasing tumor recurrence and mortality rates. We present this article in accordance with the SUPER reporting checklist (available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-31/rc).

Preoperative preparations and requirements

The patient is an elderly postmenopausal woman in generally good overall condition with no history of chronic underlying diseases. Comprehensive physical examinations are completed preoperatively, including a specialized examination by a senior and experienced gynecologist. The examination indicates: The vaginal wall is smooth, the posterior fornix has disappeared, the cervix is abnormally shaped, approximately 3 cm in size, hard in texture, and papillary neoplasms are observed on the surface, which bleed upon touch. Trimanual examination: Both sides of the parametrium are clear, with no obvious abnormalities palpated. Cervical cytology examination: atypical cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), possibility of atypical squamous cells with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (ASC-H). Human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: type 16 positive. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC): 7.79 ng/mL. Colposcopy and cervical tissue pathology examination: squamous cell carcinoma. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (plain scan + enhanced scan): cervical lesion. Lesion size: 2.8 cm × 3.0 cm × 3.4 cm, pelvic lymph nodes detected. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) (plain scan + enhanced scan): No obvious retroperitoneal lymph nodes observed. Considering biochemical tests, tumor marker examinations, and imaging studies, a comprehensive assessment is made. Based on clinical staging, open surgery is the preferred treatment option. Preoperative assessment of cardiopulmonary function is conducted. Anesthesiology evaluation indicates no contraindications for surgery.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this study and accompanying images and video. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Step-by-step description

Video 1 provides a step-by-step guide on how to perform an open radical resection for cervical cancer.

Place the patient in a supine position.

Make a lower abdominal midline incision curving to the left side near the umbilicus. The incision extends 4 fingerbreadths above the navel. Layer by layer, enter the abdomen and dissect along the grooves beside the colon on both sides to expose the pelvic cavity.

Detach the left round ligament near the pelvic sidewall, incise the peritoneum along the path of the ureter, and detach the superior pelvic diaphragm ligament on the left side.

Left pelvic lymph node dissection surgery

Detach high to ligate the pelvic funnel vessels, lift the peritoneum, isolate the iliac vessels and their branches (Figure 1), push aside the ureter at the bifurcation of the common iliac artery 3–4 cm above it (Figure 2), and remove lymphatic and adipose tissue around the anterior common iliac artery and deep around the common iliac vessels.

Follow the path of the external iliac artery, and remove the lymphatic tissue and fat from above, lateral to, behind, and between the external iliac artery and vein (Figure 3).

Lift the round ligament, clear the inguinal lymph nodes along the space, and expose the circumflex iliac vein.

Using the lateral umbilical ligament and the internal iliac artery as the inner boundary, remove the lymphatic and adipose tissue from the lateral side of the internal iliac artery and the medial side of the external iliac vein, including the lymphatic and adipose tissue around the obturator nerve (Figures 4,5).

Dissection of the rectovaginal space and uterosacral ligaments

Push the rectum downward to 3 cm below the external os of the cervix. In the lateral rectal space and the rectovaginal space (Figure 6), starting from the presacral fascia, cut through the membranous and basal parts of the sacrouterine ligaments up to the lateral side of the cervix.

Dissection of the right bladder space, rectal space, uterine artery, and cardinal ligament

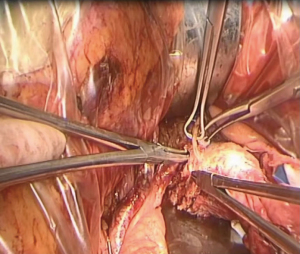

Open the anterior leaf of the broad ligament and the peritoneum reflected over the bladder. Use the uterine artery as a landmark to open the spaces lateral to the bladder and rectum down to the pelvic floor fascia. Expose the uterine artery. Clamp the uterine artery at its origin from the internal iliac artery. After dissecting the exposed deep uterine vein, remove the entire cardinal ligament from its origin at the internal iliac vein on the medial side (Figure 7), and cut the deep uterine vein and the suspensory ligaments below it.

Attach the vaginal transverse at the pelvic floor, clamp and separate the cardinal ligament.

Dissection of the bladder-vaginal space and left bladder-cervical ligament

Lift the proximal end of the uterine artery and free it to the upper medial aspect of the ureter, follow the path of the ureter, and search for the space outside its sheath. Open the bladder-cervical ligament, expose the ureteral entry into the bladder anteriorly, and push it outward (Figure 8). After cutting the posterior leaf of the bladder-cervical ligament (Figure 9), push the ureter and the bladder lateral angle away from the cervix and alongside the vagina.

Vaginal resection

Position a large right-angle clamp transversely between the bladder-vaginal space and the rectovaginal space, 25–30 mm below the external os of the cervix or 25–30 mm below the lower edge of the lesion, to clamp and close the vagina (Figure 10). Cut the vagina while it is in a straightened state, disinfect, and then suture the remaining vaginal stump. Ensure adherence to the principle of tumor-free margins.

Removal of infrarenal abdominal aortic lymph nodes and presacral lymph nodes

Position the patient with the head lowered and feet elevated. Incise the peritoneum along the anterior aspect of the right common iliac artery, extending upwards to the bifurcation of the inferior mesenteric artery (Figure 11). Strip the vascular sheath and expose the vessels, dissecting lymph nodes and fat tissue through the gaps.

Postoperative considerations and tasks

Any surgical procedure is a double-edged sword, offering therapeutic benefits while inevitably causing some degree of injury and complications. Cervical cancer surgeries, particularly the QM-C2 type of radical hysterectomy, are associated with major complications such as bladder injury, ureteral injury, and rectal injury. During the removal of the three pairs of paracervical tissues, there is a risk of damaging the pelvic autonomic nerves, which can result in direct intraoperative injuries to the bladder, ureters, and rectum. It leads to severe postoperative complications such as vesicovaginal fistula, ureterovaginal fistula, and rectovaginal fistula. Postoperatively, a urinary catheter must be retained for 3 weeks. Close monitoring of the biochemical indicators, volume, and characteristics of the abdominal drainage fluid is essential, and proactive measures to prevent infection and provide nutritional support are necessary.

Tips and pearls

Key points and techniques for lymph node dissection

To safely perform pelvic lymph node dissection, it is recommended to expose the following anatomical structures: external iliac artery and femoral artery, common iliac artery bifurcation, and ureters. Identifying these structures clearly delineates the major anatomical landmarks of the pelvic side. Whether using laparoscopy or open surgery, adhering to the principle of tumor-free margins is essential. For lymph node dissection, it is recommended to move away from the previous “tear and pull” blunt dissection method and instead perform meticulous intra-sheath dissection. Using energy devices like ultrasonic scalpels to sharply dissect lymph nodes along anatomical planes not only reduces intraoperative bleeding but also minimizes the occurrence of lymphocele and lymphatic leakage postoperatively by sealing small blood vessels and lymphatics.

Considerations for dissecting the rectovaginal space

During the dissection, which is prone to bleeding, it is crucial to proceed layer by layer and follow anatomical principles, starting from lower structures rather than higher ones. Open this space along the surface of the rectum. Prior to surgery, in addition to a gynecological examination, use CT and MRI to assess for invasion of the posterior vaginal wall. Dissect this space down to 25–30 mm below the external os of the cervix or the lower edge of the lesion to ensure sufficient length for vaginal resection. Free both sides of this space towards the medial edge of the bilateral uterosacral ligaments. In the middle segment of the uterosacral ligament, completely free the lateral wall of the rectum until reaching the presacral fascia, exposing the uterosacral ligaments along their entire length.

Lateral to the uterosacral ligament lies the hypogastric nerve. To preserve the nerve, it can be gently retracted outward during surgery.

Technical points for dissecting the bladder and rectal side spaces

The bladder side space and rectal side space are vertically symmetrical, with the uterine artery located between them, forming a “mirror image” known as the “eagle eye”. Proper dissection is necessary to expose the parametrium and the cardinal ligament. For dissecting the bladder space, elevate the lateral umbilical ligament and dissect downwards between the uterine artery and the superior vesical artery to the pelvic diaphragm. Dissecting the rectal space from superficial to deep reveals the uterine artery, superficial uterine veins, and deep uterine veins. Improper handling can easily damage these veins, leading to significant hemorrhage (10).

Technical points for dissecting the vesicocervicovaginal space

The space is located below the vesicocervical space, whose tissue is relatively loose and easy to separate. The depth of dissection should be 25–30 mm below the external cervical os or the lower margin of the lesion. On both sides, it extends to the vaginal sidewalls (or the medial leaf of the vesicocervicovaginal ligament at the subknee level). During dissection, care should be taken to avoid injury to the posterior bladder wall. Remove the superficial layer (anterior leaf) of the vesicocervicovaginal ligament to expose the cervical segment of the ureter, commonly referred to as “tunneling”. Fully expose the Grunling space, the ventral vesicocervical space, the vesicovaginal space, and the bladder side space. Thin out the superficial layer of the vesicocervicovaginal ligament and remove its medial leaf while avoiding injury to the ureter. Preserve as much tissue and the vascular network on the ureter as possible. Completely free the bladder and cervical segment of the ureter from the lateral cervical and paravaginal tissues to facilitate a more thorough resection of the cardinal and paravaginal tissues. In elderly women, postmenopausal vaginal atrophy and reduced elasticity often make it challenging to achieve an adequate resection. After removing the uterus, check the vaginal stump and resect additional vaginal tissue if necessary.

Technique for lower abdominal aortic lymph node dissection

The lymph nodes adjacent to the lower abdominal aorta extend from the level of the mesenteric artery to the iliac vessels. Completely remove lymph nodes and fat around the aorta, as well as those around the inferior vena cava. After identifying the ureter and ovarian vessels, pull them laterally. Most lymph nodes on the right side of the abdominal aorta are located above the inferior vena cava and can be easily dissected from the vein. Be cautious of small veins entering the inferior vena cava within the lymph node tissue and avoid causing damage.

Discussion

The primary treatment modalities for primary cervical cancer encompass surgery, radiotherapy (RT), and concurrent chemoradiotherapy. The reported recurrence rate following initial treatment ranges from 25% to 61%. Recurrence patterns in cervical cancer are categorized into pelvic recurrence and extrapelvic recurrence, with pelvic recurrence further subdivided into central and peripheral types. For patients who undergo surgery for early-stage cervical cancer, the sole risk factor for subsequent disease recurrence is a tumor maximum diameter of 4 cm or greater. It has been established that a tumor maximum diameter exceeding 4 cm is a factor affecting progression-free survival (PFS). Following laparoscopic total hysterectomy, patients exhibit a higher incidence of peritoneal carcinomatosis. The ConCerv and SHAPE studies have provided evidence-based support for the feasibility and safety of simple hysterectomy in early-stage, low-risk cervical cancer patients. For patients desiring fertility preservation, conservative surgery may offer benefits such as increased pregnancy rates and reduced rates of miscarriage and preterm birth, making it a worthwhile consideration. For non-fertility-preserving patients, conservative surgery has demonstrated improvements in short-term urinary function and long-term sexual function. In clinical practice, we anticipate further clinical studies to substantiate the role of conservative surgery in early-stage, low-risk cervical cancer. Surgery remains the primary treatment modality for early-stage cervical cancer. Surgery remains the primary treatment modality for early-stage cervical cancer. Vaginal surgery, due to the anatomical characteristics of the vagina, presents challenges such as a narrow surgical field and difficult exposure, requiring high standards of anesthesia and muscle relaxation. Although vaginal surgery may avoid the risk of tumor dissemination associated with pneumoperitoneum, cervical cancer patients often present with parametrial and pelvic adhesions, particularly when the uterus is enlarged, making the procedure more challenging and increasing the risk of complications and surgical failure. The learning curve for vaginal surgery is prolonged, limiting its widespread adoption, and it is currently not the preferred surgical approach for cervical cancer. Laparoscopic minimally invasive surgery offers advantages including clear visualization, precise anatomical identification, reduced intraoperative blood loss, faster postoperative recovery, shorter hospital stays, and improved cosmetic outcomes. Open surgery, on the other hand, has broader indications, lower costs, requires no specialized equipment, results in less thermal injury, fewer urinary complications, and may more easily adhere to oncological principles, potentially offering survival benefits. Surgery demonstrates favorable efficacy in the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer. According to the 2022 NCCN guidelines (11), open surgery is recognized as the classic approach for curative treatment of cervical cancer. The Piver classification (12) lacks standardized surgical procedures and scope of resection, making it challenging to assess oncological outcomes and surgical complications postoperatively. For this reason, the current surgical classification uses the QM system. Under this system, traditional extensive hysterectomy corresponds to QM-C2 classification under QM. The QM-C2 procedure is an extensive hysterectomy that does not preserve autonomic nerves, with the standard being the complete removal of paracervical tissue. The requirements are: (I) the uterine artery is severed at its origin. (II) The ureteral segment near the cervix is fully mobilized. (III) The lateral paracervical tissue (cardinal ligament) is removed along the medial side of the internal iliac vessels down to the pelvic floor. (IV) The ventral paracervical tissue (vesicouterine ligament) is removed at the level of the bladder wall (ureterovesical junction) on the ventral side of the cervix, with the bladder branches of the inferior hypogastric plexus being severed. (V) The dorsal paracervical tissue (uterosacral ligament) is removed along the surface of the sacrum on the dorsal side of the cervix, including the sacral splanchnic nerves within it. (VI) Partial paravaginal tissue is removed. (VII) The length of the vaginal resection is determined by the extent of tumor invasion into the vagina, generally removing at least 25 mm of vaginal tissue from the cervix or the tumor margin. Completely excise and sharply dissect lymph nodes; systematically expose structures layer by layer and in compartments to minimize intraoperative injury; disinfect the vaginal stump multiple times after removing the cervix. These three points are all essential requirements of this surgery. In traditional open surgery, it is difficult to identify blood vessels and nerves, making it impossible to achieve standardized and homogenized resection of paracervical tissues. This results in insufficient removal of paracervical tissues, increasing intraoperative and postoperative complications and postoperative tumor recurrence rates. The cervical regions are rich in blood vessels and pelvic nerves. Although laparoscopy provides a clearer view of pelvic structures, there is currently no compelling experimental data to overturn the conclusions of the LACC study (10), and open surgery remains the gold standard. Compared to the meticulous techniques of laparoscopic surgery, open surgery should place greater emphasis on anatomical exposure and layer-by-layer dissection, adhering to the principles of space surgery. To ensure optimal intraoperative visualization during open surgery, the abdominal incision should adequately expose the pelvic cavity, extending from the superior margin of the pubic symphysis to 3 cm above the umbilicus. Following layered entry into the abdominal cavity, dissection proceeds according to anatomical planes. Ultrasonic scalpels and other electrical instruments are utilized for thorough hemostasis, ensuring minimal or no bleeding in the surgical field. Finger palpation and manipulation can be employed to identify tissue planes, reducing the risk of sharp instrument-induced injury. Direct visual perception allows for clearer tissue differentiation, offering a distinct advantage for medical institutions without access to high-definition imaging capabilities. There is ongoing debate regarding the optimal tumor size threshold for minimally invasive approaches, with the question of whether tumors less than 2 cm or less than 3 cm are suitable still requiring validation through high-level prospective studies. This ensures full exposure of paracervical tissue structures and specific anatomical landmarks, optimizing surgical procedures to minimize trauma and reduce complications. The optimal treatment strategy for cervical cancer patients should be individualized based on factors such as age, tumor stage, fertility desires, and baseline conditions. We anticipate further high-level prospective research data to guide the future direction of surgical management for early-stage cervical cancer.

Conclusions

The technique of space dissection is applied from laparoscopy to the open surgical approach. This method not only meets the recommended surgical standards of guidelines but also reduces intraoperative bleeding, trauma, and postoperative complications, ensuring surgical safety. It further facilitates the implementation of standardized surgical procedures, promotes the homogenization of surgical treatment standards, and contributes to the global strategic action to eliminate cervical cancer.

Acknowledgments

The video was awarded the third prize in the Fourth International Elite Gynecologic Surgery Competition (2024 Masters of Gynecologic Surgery).

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Gynecology and Pelvic Medicine for the series “Award-Winning Videos from the Fourth International Elite Gynecologic Surgery Competition (2024 Masters of Gynecologic Surgery)”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SUPER reporting checklist. Available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-31/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-31/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-31/coif). The series “Award-Winning Videos from the Fourth International Elite Gynecologic Surgery Competition (2024 Masters of Gynecologic Surgery)” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this study and accompanying images and video. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Singh D, Vignat J, Lorenzoni V, et al. Global estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2020: a baseline analysis of the WHO Global Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative. Lancet Glob Health 2023;11:e197-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu ZC, Li ZX, Yang Zhang, et al. Interpretation on the report of Global Cancer Statistics 2020. Journal of Multidisciplinary Cancer Management 2021;2:1-13. (Electronic Version).

- WHO. WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention [EB/OL]. (2021-07-06) [2021-07-18]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/06-07-2021-q-and-a-screening-and-treatment-cervicalpre-cancer-lesions-for-cervical-cancer-prevention

- Wu ES, Jeronimo J, Feldman S. Barriers and Challenges to Treatment Alternatives for Early-Stage Cervical Cancer in Lower-Resource Settings. J Glob Oncol 2017;3:572-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Querleu D, Cibula D, Abu-Rustum NR. 2017 Update on the Querleu-Morrow Classification of Radical Hysterectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24:3406-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- COGA. Quality control criteria for surgical treatment of Cervical cancer: QM-C2 extensive hysterectomy. Chinese Journal of Practical Gynecology and Obstetrics 2022;38:66-72.

- Levenback C, Coleman RL, Burke TW, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node identification in patients with cervix cancer undergoing radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:688-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin Z. Interpretation of 2009 NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cervical Cancer. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2009;36:167-8.

- Abu-Rustum NR, Yashar CM, Bean S, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Cervical Cancer, Version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020;18:660-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koninckx PR, Puga M, Ussia A, et al. Regarding: “The LACC Trial and Minimally Invasive Surgery in Cervical Cancer”. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2020;27:239-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng Q, Lv W. Interpretation of NCCN guidelines for cervical cancer, version 1. 2022. Journal of Practical Oncology 2022;37:205-14.

- Piver MS, Rutledge F, Smith JP. Five classes of extended hysterectomy for women with cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1974;44:265-72. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Li Z, Zhang Y, Wen Y, Zuo X. Treatment of cervical squamous cell carcinoma with transabdominal lymph node resection and QM-C2 surgery: a surgical technique. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2024;7:37.