Missed diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse complicated with cervical cancer: a retrospective case series of five patients and review of literature

Highlight box

Key findings

• Coexistence of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and cervical cancer poses a diagnostic challenge.

• Timely cervical biopsy is crucial for POP patients with new cervical organisms, cervical erosion, or concurrent local infections.

What is known and what is new?

• POP is prevalent in older women, impacting the pelvic structure.

• Cervical cancer can be masked by POP symptoms, leading to potential misdiagnosis.

• Appropriate diagnostic measures such as pelvic examinations, biopsies, and imaging studies are necessary to exclude cervical malignant lesions before surgery in POP patients.

• Multidisciplinary approach involving gynecologists, oncologists, and pelvic floor specialists is necessary for optimal management.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for cervical cancer in patients with POP.

• Early detection and timely treatment are crucial for improving outcomes in elderly patients.

• Need for standardized guidelines for the management of cervical cancer in the presence of POP.

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a common condition in women, with estimates suggesting it occurs in 40% to 67% of parous women (1-3). While the occurrence of concurrent uterine prolapse with cervical cancer is not common (4). One of the common complications of POP, particularly procidentia, is the ulceration of the most dependent area of the prolapse, which is frequently the cervix (5). Chronic irritation from long-standing POP may lead to dysplasia and human papillomavirus (HPV)-independent carcinoma, representing only 5% of cervical cancers (6). However, the continuous injury of the cervical epithelium may contribute to the neoplastic process (7). Women with uterine prolapse are at an increased risk of chronic inflammation and direct mechanical irritation of the prolapsed areas, which may predispose them to a higher risk of cervical cancer development (4,8). The relationship between POP and non-HPV Papanicolaou (Pap) smear abnormalities is significant. A study found that the rate of non-HPV-associated abnormal Pap smears was higher in the POP group than in the non-POP group, and the rate of non-HPV Pap smear abnormality was significantly associated with increasing prolapse stage. This poses challenges for diagnosis and management (9). However, early detection and proper management of cervical cancer in patients with POP are crucial. A study by Wan et al. (10) highlighted the risk of missing a malignancy in surgical specimens following hysterectomy for uterine prolapse if routine pathological examination is not performed. The study found that 61.25% of cases had abnormal findings, including premalignant and malignant uterine conditions (11). However, one study showed that cervical cancer patients with complete uterine prolapse had more favorable survival outcomes with surgery-based treatment (12). Common complications include delayed treatment, invasive cancer progression, and complex surgical management. Early detection and tailored treatment strategies are crucial to improve patient outcomes (13,14). Additionally, cervical cancer complicating POP in elderly patients necessitates a multidisciplinary approach (15), the literature review examines the challenges in diagnosis due to overlapping symptoms. The literature review from 1989 to 2024 identified 22 case reports involving 26 patients (average age: 68.31 years), with the majority (83.36%) at advanced stages of prolapse (Stage III or IV). The predominant cancer types were cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), representing 61.54% of cases, followed by vaginal SCC at 15.38%. Endometrial cancer was diagnosed in 11.54% of patients, with 7.69% of these cases being endometrioid carcinoma, and fallopian tube carcinoma accounted for 3.85% of the cases. On average, there was a 14.18 years delay from prolapse onset to cancer diagnosis. Treatments included hysterectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy. Among these cases, 42.30% had favorable outcomes, while 15.38% experienced adverse events, including two fatalities (Table 1) (5,7,14-33). This underscores the importance of swift, precise diagnostics and a multidisciplinary approach, especially in older patients due to symptom overlap.

Table 1

| Case | Author, year | Study type | Patient age (years) | Cancer type | Prolapse duration | Prolapse stages | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rao, 1989 (16) | Case reports | 65 | Squamous cell carcinoma of vagina | 2 years | Stage III | Radical vaginal hysterectomy with total vaginectomy with cystcoeleand entero-rectocele repair with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | No clinical evidence of recurrence |

| 2 | Luna, 1996 (17) | Case reports | 60 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix (Stage IIB) | 12 years | Stage III | Radiation therapy, hysterectomy | Developed pulmonary metastasis |

| 3 | da Silva, 2002 (18) | Case reports | 69 and 73 | Epidermoid carcinoma | NA | Stage III and Stage IV | Radical vaginal hysterectomy and radiotherapy | One patient lost to follow-up, the other alive with no signs of disease after 2 years |

| 4 | Batista, 2009 (19) | Case reports | 73 | Verrucous epidermoid carcinoma | 16 years | Stage III | Surgery and radiotherapy | No recurrence after 2 years |

| 5 | Loizzi, 2010 (20) | Case reports | 86 | Squamous cell carcinoma of cervix | 20 years | Stage III | Vaginal hysterectomy | Patient died of pulmonary embolism |

| 6 | Cabrera, 2010 (21) | Case reports | 54 | Squamous cell carcinoma of cervix (Stage IB2) | NA | Stage IV | Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy | No recurrence 10 months after treatment |

| 7 | Kim, 2013 (22) | Case reports | 80 | Squamous cell carcinoma of vagina | 20 years | Stage III | NA | Died from progression of disease one month after diagnosis |

| 8 | Wang, 2014 (23) | Review and case reports | 61 | Squamous cell carcinoma of vagina | 30 years | Stage III | Surgical treatment with radiotherapy | No recurrence during 4 years of follow-up |

| 9 | Pardal, 2015 (14) | Case reports | 74 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix | 20 years | Stage IV | Vaginal hysterectomy, open bilateral iliopelvic lymphadenectomy, and radiotherapy with quimiosensibilisation | Progression of the disease |

| 10 | Vanichtantikul, 2017 (24) | Case reports | 87 | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma (Stage IV B) | 10 years | Stage IV | Radiotherapy and pessary | After palliative radiotherapy for the primary tumor, the patient showed symptom recovery and developed Grade 2 dermatotoxicity, which resolved within 3 months. At 6 months post-radiation, the patient was asymptomatic and choose to receive best supportive care. A support pessary was placed to treat the predominance of other pain (POP) |

| 11 | Dawkins, 2018 (15) | Case reports | 72 | Squamous cell carcinoma of cervix | 7 years | Stage IV | Pessary insertion, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy | Successful outcome |

| 12 | Chung, 2018 (25) | Case reports | 72 and 67 | Stage IIA2 invasive squamous cell cervical cancer and uterine carcinosarcoma | NA | Stage IV | Abdominal and vaginal approaches and with concurrent pelvic reconstruction | NA |

| 13 | Constantin, 2019 (26) | Case reports | 62 | Metastatic endometrial cancer | NA | Stage IV | Colpo-hysterectomy according to Rouhier | No recurrence after 17 months |

| 14 | Cola, 2020 (27) | Case reports | 81 | Squamous cell carcinoma of vagina | NA | Stage IV | Anterior colpectomy, retrograde hysterectomy, transvaginal levator ani plication | Successfully achieved without complications |

| 15 | Jacomina, 2021 (28) | Case reports | 32 | Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix (Stage IIIC1r) | NA | Stage IV | Chemotherapy and radiation therapy | No clinical evidence of disease and recurrence |

| 16 | Evangelopoulou, 2021 (5) | Case reports | 81 | Cervical squamous cell carcinoma (FIGO Stage IIIB) | 15 years | Stage IV | Palliative chemotherapy plus radiotherapy | Patient’s general condition deteriorated, and 3 months after the diagnosis, the patient passed away |

| 17 | Onigahara, 2021 (29) | Case reports | 65 | Endometrioid carcinoma (Grade 1) | NA | Stage III | Trachelectomy, anterior-posterior colporrhaphy, and vaginal apex suspension | No recurrence after 6 months |

| 18 | Estevinho, 2021 (7) | Case reports | 74 | Squamous cell carcinoma of cervix (Stage FIGO IIIA) | 10 years | Stage IV | Radiotherapy | Patient died after a month |

| 19 | Lee, 2022 (30) | Case reports | 74 | Verrucous-type squamous cell carcinoma of cervix (Stage IIIC1r) | 30 years | Stage IV | Chemoradiotherapy, hysterectomy, and uterosacral ligament suspension | Disease-free at 19 months postoperative follow-up |

| 20 | Niu, 2022 (31) | Case reports | 62 and 50 | Cervical carcinoma; fallopian tube carcinoma; endometrial carcinoma | Case 1: 9 months; Case 2: NA; Case 3: 4 months | Stage III | Surgery for both tumor and prolapse | The study suggests that following existing clinical methods and diagnosis and treatment processes can lead to standardized initial treatment that addresses both the tumor and prolapse, potentially improving the long-term outcomes and quality of life of patients |

| 21 | Ota, 2020 (32) | Case reports | 71 | Squamous cell carcinoma of cervix (Stage IB1) | NA | Stage III | Radical hysterectomy and immediate sacral colpopexy using autologous fascia lata | No recurrence after 20 months |

| 22 | Wang, 2023 (33) | Case reports | 69 | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | NA | Stage III | Transvaginal hysterectomy, repair of anterior and posterior vaginal walls, ischium fascial fixation and repair of an old perineal laceration, bilateral adnexectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, para-aortic lymphadenectomy | No recurrence after 11 months |

POP, pelvic organ prolapse; NA, not applicable; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The retrospective analysis of five Chinese postmenopausal women further emphasizes diagnostic challenges, disease progression, and the significance of vigilant screening and tailored care to prevent missed diagnoses in POP patients, supporting a holistic management strategy. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE and AME Case Series reporting checklists (available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-19/rc).

Methods

Using a retrospective study design, we performed a case series study evaluating Chinese women with missed diagnosis of POP complicated with cervical cancer between June 2020 and June 2024. Data were obtained from electronic medical records, encompassing details such as age, obstetric history, body mass index (BMI), symptoms, medical history, laboratory findings, imaging studies, surgical procedures, operative details, complications, postoperative pathology reports, and postoperative diagnoses. Follow-up data were also collected after surgery to evaluate recurrence rates.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval was waived by the ethics committee as it was retrospective case series and no patient identifiable information was used. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Statistical analysis

All the analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 software (SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive methods were employed to summarize the data. Continuous data were presented as medians and ranges to account for skewness, while categorical data were reported as percentages. No inferential statistics were used in the analysis due to the case series design.

Results

In this retrospective case series study, five Chinese women with missed diagnosis of POP complicated with cervical cancer at our hospital were analyzed. The median age was 75 years (range, 71–86 years), and median BMI was 20.00 kg/m2 (range, 14.67–28.70 kg/m2). The POP duration varied from 1 to 50 years, with a median of 15 years. Comprehensive information on clinical symptoms, past history, gynecological examinations, laboratory biomarkers, imaging examination and various abnormalities are presented in Table 2 for all patients. Their POP-quantification and diagnosis are presented in Table 3.

Table 2

| Case | Ages (years) | Gravida | Parity | BMI (kg/m2) | POP duration (years) | Past history | Clinical symptoms | Gynecological examination | Laboratory tests | Pap test | HPV test | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 86 | 2 | 1 | 14.67 | 50 | None | Intermittent vaginal bleeding, vaginal ulcers, lumbosacral pain, dysuria, occasional urine leakage | Severe vaginal prolapse: bilateral wall involvement, ulcerated uterus, covered in white moss, strong odor | CEA =2.61 ng/mL, AFP =2.05 ng/mL, CA19-9 <0.60 U/mL, CA-125 =8.97 U/mL | Negative | Negative | Pelvic organ prolapse; the formation of uterine body and adjacent skin fistula; and the formation of multiple abscesses in pelvic floor soft tissue |

| 2 | 71 | 3 | 3 | 28.7 | 15 | 15 years uterine prolapse, 1 year knee arthroplasty | Irregular vaginal bleeding for over 2 months | Mild cervical erosion | CEA =2.58 ng/mL, AFP =3.90 ng/mL, CA19-9 <0.81 U/mL, CA-125 =10.97 U/mL | Negative | Negative | Not available |

| 3 | 74 | 3 | 2 | 24.6 | 1 | Hypertension, 20 years laparoscopic cholecystectomy | Vaginal prolapse and persistent perianal discomfort for 1+ year | Enlarged cervix with mild erosion | Not available | Positive for LSIL | Positive for high-risk types (HPV18, HPV52, HPV66) | Not available |

| 4 | 85 | 8 | 5 | 18.7 | 3 | 50 years abdominal surgery for intestinal tuberculosis, 40 years surgery for intestinal adhesions, 5 years surgery on the right femur | Vaginal mass, worsened in recent year, leading to urinary difficulties and unrelieved symptoms | Mild cervical hypertrophy with ectropion present | Not available | Positive for HSIL | Positive | Not available |

| 5 | 75 | 6 | 3 | 20 | 15 | Right wrist fracture (6 years ago) with plate fixation, plate still in situ; untreated cataracts (9 years duration); allergic to penicillin and streptomycin | Increased urinary frequency and urgency | Old perineal scar, atrophic cervix | CEA =2.00 ng/mL, AFP <1.3 ng/mL, CA19-9 79.6 U/mL, CA-125 =24.3 U/mL | Positive for HSIL | Positive for high-risk types (HPV18 and HPV51) | Endometrial calcification; minimal fluid in the uterine cavity; and weak echoes in the lower uterine segment and cervical canal |

BMI, body mass index; POP, pelvic organ prolapse; Pap, Papanicolaou; HPV, human papillomavirus; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CA-125, carbohydrate antigen 125; LSIL, low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Table 3

| Case | Points | Cystocele | Uterine prolapse | Rectocele | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | Ba | C | Gh | Pb | Tvl | Ap | Bp | D | ||||

| 1 | +1 | +6 | +6 | 7 | 2.5 | 7 | −1 | +6 | +5 | IV | IV | IV |

| 2 | −1 | −1 | +2.5 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 8 | −2 | −2 | −2 | II | III | I |

| 3 | 0 | +4 | −1 | 5 | 2.5 | 7 | −2 | −2 | −2 | III | II | I |

| 4 | 0 | +4 | 0 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 6 | −1 | −1 | −1 | IV | II | II |

| 5 | 0 | +4 | +1 | 3.5 | 2.5 | 6 | −1 | −1 | −1 | IV | II | II |

Preoperatively, two patients had negative HPV tests and normal Pap smears, while the remaining three had positive HPV or concerning Pap smear results. No malignancy or atypical cells were found in cytology. A biopsy on Case 5 confirmed chronic cervicitis along with degeneration of the squamous epithelium and inflammatory infiltration within the cervical canal.

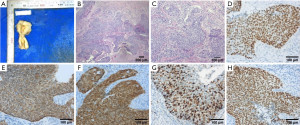

Preoperatively, Case 1 underwent treatment for an ulcer and abscess with antibiotics and potassium permanganate baths for infection control and wound healing. Surgical procedures performed included vaginal hysterectomies, colpocleisis, perineorrhaphies, excision of a cervical neoplasm, dilation and curettage, laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, laparoscopic lateral suspension. Case 1 had a minor bladder injury, and three patients underwent quick frozen pathology examinations. The operation times ranged from 47 to 120 minutes (median: 93 minutes), blood loss was 50 to 600 mL (median: 50 mL), and urinary catheters were removed after 3 to 15 days (median: 3 days). The postoperative hospital stay lasted 4 to 8 days (median: 4 days) (Table 4). For Case 1, Figure 1 combines preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of Stage IV prolapse with an ulcerated abscess, the postoperative specimen, and pathology results (SCC). Cases 2–5 each have a postoperative specimen and histopathology image (Figures 2-5), demonstrating effective surgical treatment for cervical cancer. No adjuvant chemotherapy was needed in any case. In Case 1, a recommendation for post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy was made; however, the patient’s family declined due to her age and opted for regular follow-up in the outpatient clinic every 3 months instead. All patients were recommended to follow up in the outpatient clinic every 3 months, with a median postoperative follow-up of 11 months (range, 2–48 months). During this follow-up period, no recurrences were reported (Table 4).

Table 4

| Case | Operation | Duration of operation (min) | Intraoperative bleeding (mL) | Complication | Intraoperative frozen sectionpathology diagnosis | Postoperative pathology diagnosis | Post-operative diagnosis | Postoperative urinary catheter removal (days) | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vaginal hysterectomy, colpocleisis, perineorrhaphy | 120 | 600 | Injury of bladder | Not performed | Macroscopy: a high to medium differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, immunohistochemistry: P63 (+), CK5/6 (+), P16 (−) and ki67 all at a rate of 30% | Stage IV pelvic organ prolapse, cervical squamous epithelial carcinoma IIB, simple hyperplasia of the endometrium, endometrial polyps, and cervical and vaginal infection | 15 | 29, no recurrence |

| 2 | Vaginal hysterectomy, colpocleisis, perineorrhaphy | 70 | 50 | None | Endometrial and cervical endometrial polyps; CIN grade III with glands involvement | Macroscopy: a poorly-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, immuno-histochemistry: p63 (+), CK5/6 (+), p16 (+), Ki67 and P40 (+) all at a rate of 65% | Stage III uterine prolapse, squamous cell carcinoma IB1, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III, endometrial polyps, cervical endometrial polyps, and hypertension | 3 | 48, no recurrence |

| 3 | Excision of cervical neoplasm, dilation and curettage, vaginal hysterectomy, laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, laparoscopic lateral suspension, perineorrhaphy | 93 | 50 | None | Cervical endometrial polyp with squamous metaplasia, CIN grade II, and glandular involvement, with a focal micro-invasive lesion measuring 1 mm in width and depth | Multiple leiomyomas with degeneration and calcification, adenomyosis, endometrial cysts, chronic cervicitis, and inflammation of the fallopian tubes with mesosalpinx endometriosis; IHC staining negative expression of CD10 and ALK | Stage III anterior vaginal wall prolapse, stage II uterine prolapse, stage IA1 cervical cancer, cervical HPV infection, and hypertension | 3 | 11, no recurrence |

| 4 | Vaginal hysterectomy, colpocleisis, perineorrhaphy | 47 | 50 | None | Not performed | Chronic cervicitis and endocervicitis; widespread CIN III lesions; microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma; VaIN II and III lesions; squamous epithelial hyperplasia | Stage IV anterior vaginal wall prolapse, stage II uterine prolapse, chronic cervicitis and endocervicitis with CIN III lesions, microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma, VaIN II and III lesions, squamous epithelial hyperplasia, and HPV infection | 3 | 6, no recurrence |

| 5 | Vaginal hysterectomy, colpocleisis, perineorrhaphy | 105 | 50 | None | Isolated squamous epithelium with severe atypical hyperplasia was found with papilloma-like growth | Chronic cervicitis/CIN III; microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma (≤1 mm depth) involving endometrium and <1/2 myometrium; no parametrial or vaginal involvement; VIN I in perineal body; and severe dysplasia in cervical canal | Stage IV anterior vaginal wall prolapse, stage II uterine prolapse, old perineal scar, severe dysplasia (CIN III) of the cervix, and HPV infection | 3 | 2, no recurrence |

CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; IHC, immunohistochemistry; CD10, cluster of differentiation 10; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; HPV, human papillomavirus; VaIN, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia.

Discussion

This study highlights the missed diagnosis of POP complicated by cervical cancer, a challenging condition often overlooked. By examining clinical presentations, diagnostic challenges, and treatment outcomes, it rises awareness and emphasize the need for improved diagnostic strategies, particularly in elderly patients with overlapping symptoms. It underscores the importance of vigilant assessment to prevent misdiagnosis and ensure timely management for optimal patient care.

In literature, there is limited evidence on the prevalence of missed diagnosis of POP complicated with cervical cancer. The risk of unanticipated uterine cancer and cervical cancer in women undergoing hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse were 0.53% for uterine cancer and 0.09% for cervical cancer according to American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database from the 2015–2018 (34). Mahnert et al. (35) used statewide data in Michigan and found an incidence of 0.3% for cervical cancer in a cohort of 670 patients undergoing hysterectomy for prolapse. In an underscreened population, another database from the 2007–2019 showed the rates of cervical dysplasia or cancer were 0.41% (3/729) for patients undergoing hysterectomy for POP (36).

In the context of cervical cancer, missed diagnosis can lead to delayed treatment, which can result in disease progression and poorer prognosis. POP patients with cervical cancer had a mean age of 74 years at diagnosis, and 20% of cases being Stage III cervical cancer and all cases having Stage III–IV uterovaginal prolapse (13). Delayed diagnosis and advanced stage at diagnosis can limit treatment options and decrease the likelihood of successful treatment outcomes. Furthermore, missed diagnosis of cervical cancer in the context of POP can also impact the choice of treatment. Surgical intervention is often required for both the tumor and the prolapse, and missed diagnosis may result in the need for secondary surgeries, which can affect the patient’s quality of life (31). Additionally, missed diagnosis can lead to inadequate preoperative evaluation and planning, potentially affecting the surgical approach and outcomes (21). Based on the general understanding of missed diagnosis in cervical cancer and the challenges associated with managing POP and cervical cancer concurrently, it is reasonable to assume that missed diagnosis can have negative consequences for patient outcomes. Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for timely and appropriate treatment, which can improve prognosis and overall patient outcomes. Due to preoperative missed diagnosis of cervical cancer in patients with POP, the choice of surgical method may be affected, and a second surgery may be required, which may even affect postoperative treatment and efficacy. Four out of five patients (4/5) in this study were all misdiagnosed with cervical cancer before surgery, and two out of five patients (2/5) were diagnosed with cervical cancer after intraoperative freezing. It is important for all patients to receive postoperative supplementary treatment and regular follow-up, it should be taken seriously by clinical doctors.

The common reasons for missed diagnosis of POP complicated with cervical cancer include inadequate evaluation of abnormal Pap smears or cervical biopsies, failure to perform indicated procedures such as conization or biopsy, misinterpretation of pathology results, lack of preoperative screening tests, and failure to biopsy a gross cervical lesion. These factors contribute to missed opportunities for more timely diagnosis and highlight the importance of adhering to established guidelines for cervical cancer detection (37,38).

Older age has been identified as a risk factor for delayed diagnosis of uterine cervical lesions (39). A Pap smear during the pre-invasive detectable phase was significantly negatively associated with the development of invasive cervical cancer in women over 65 years old (40). Advanced age was associated with a reduced likelihood of adequate screening for cervical cancer (41). Menhaji et al. (9) found that the rate of non-HPV-associated abnormal Pap smears was higher in the POP group than in the non-POP group. It suggests that regular screening and evaluation are crucial, especially for elderly POP patients over 70 years old. Wang et al. (42) also supports the importance of regular screening in older age groups. But elderly women, especially those over 75 years old, are less likely to have had Pap testing (43). It is important for healthcare practitioners to consider age-related factors and ensure appropriate screening and evaluation for older women. This highlights the importance of patient education and awareness about cervical cancer screening. This underscores the importance of healthcare providers making efforts to improve attendance rates of Pap smear screening in elderly women.

Abnormal vaginal bleeding is a significant risk factor for delayed diagnosis of cervical cancer (39). Several studies identified post-menopausal bleeding as a high-risk symptom for cervical cancer, which could be mistaken for benign symptoms in patients with POP. Therefore, it is crucial to consider these atypical symptoms and conduct thorough evaluations in patients with POP to avoid missed diagnoses of cervical cancer (44,45). We should be vigilant for elderly woman with POP who developed new-onset vaginal bleeding (15). Chronic inflammation caused by POP and friction may contribute to missed diagnosis of cervical cancer.

One study found that poor cervical cytology before colposcopy, unsatisfactory colposcopy, and positive high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) detection were risk factors for missed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2+ in low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) pathologically diagnosed by colposcopy-assisted biopsy (46). Incomplete evaluation of cervical dysplasia or microinvasion on biopsy and false-negative cervical cytology were identified as risk factors for improper simple hysterectomy in cervical cancer patients (47,48). Additionally, a retrospective review found that missed opportunities for screening and early diagnosis of cervical cancer were associated with lack of prior visits recorded, absence of prior cytology, and failure to adhere to screening guidelines (49).

Another reason for missed diagnosis is the delay in seeking medical care. Reis et al. (50) identified obstacles to seeking medical care as a theme in their qualitative study on the experiences of women with advanced cervical cancer. A study found that women with POP lack awareness about cervical cancer and screening services, leading to delayed care-seeking behavior. This finding suggest that healthcare providers should sensitize women with POP to seek timely screening and treatment services for cervical cancer (51). Furthermore, the complexity of managing patients with both POP and cervical cancer can contribute to missed diagnosis. Also, a common reason for missed diagnosis of POP complicated with cervical cancer is the similarity of symptoms between the two conditions. Both conditions can present with symptoms such as abnormal vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, and a sensation of a bulge or protrusion in the vagina. These overlapping symptoms can lead to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of cervical cancer in the presence of POP. It is important for healthcare providers to maintain a high index of suspicion and consider further evaluation, such as imaging or biopsy, to rule out cervical cancer in patients with POP (52). Adhering to established diagnostic protocols and guidelines is essential to prevent missed diagnoses. It is important for healthcare providers to be aware of these risk factors and ensure comprehensive evaluation and appropriate screening for patients with POP to avoid missed diagnoses of cervical cancer. Early detection and timely intervention are crucial for improving outcomes in these cases.

Dawkins et al. (15) highlighted the importance of a multidisciplinary approach involving urogynecologists, gynecologic oncologists, and radiation oncologists in managing cervical cancer complicating POP. Ota et al. (32) proposed a combined surgery for cervical cancer and POP. Therefore, a multidisciplinary approach is necessary for proper management. Studies have explored various treatment approaches for cervical cancer in patients with POP. A multidisciplinary approach, including chemoradiotherapy followed by radical hysterectomy, has shown success in treating these conditions (7). Surgery-based treatment may also have a positive effect on survival outcomes in cervical cancer patients with complete uterine prolapse (1). Our cases, consistent with Yang et al. (53), emphasize the need for rigorous cervical cancer screening, especially in those undergoing gynecological diagnostic procedures. The case presented by Zhu et al. (54) underscores the crucial role of employing innovative therapies, such as brachytherapy, when confronting intricate clinical scenarios. Despite this, a standardized optimal management protocol remains elusive.

Our cases, along with others in the literature, demonstrate that late-stage diagnoses often necessitate more aggressive therapies and can lead to less favorable outcomes (7,13). The patient education and counseling strategies outlined by Nemirovsky et al. (55) are vital, as they ensure patients have a comprehensive understanding of their condition and potential complications. Additional research and studies are needed to yield more precise information on prognosis outcomes specifically in this patient population.

The American Urogynecologic Society Prolapse Consensus Conference highlighted the importance of assembling interdisciplinary teams to address the complex scientific dimensions of POP (56). Dällenbach et al. (57) highlights the need for a blend of scholarly understanding and surgical dexterity in treating anterior POP, illustrating the challenges of detecting coexisting conditions. Both studies underscore the value of embracing a holistic perspective that recognizes the interconnection between gynecological and urological factors. Such collaborative endeavors can shed light on the optimal handling of POP and its associated complications, including cervical cancer (56).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the missed diagnosis of cervical cancer in patients with POP is a significant concern. Regular screening and evaluation should be conducted in these patients to ensure early detection and appropriate management, especially for elderly POP patients over 70 years old. Preoperative screening methods may have limitations in detecting cervical abnormalities in POP patients. Attention should be paid to POP patients with new cervical organisms, cervical erosion, and concurrent local cervical infections, and timely cervical biopsy should be performed. It is important for healthcare providers to be aware of the possibility of cervical cancer in patients with POP. Accurate diagnosis, appropriate screening, and tailored treatment strategies are crucial in managing cervical cancer in the presence of POP. A multidisciplinary approach involving urogynecologists, gynecologic oncologists, and radiation oncologists may be necessary for optimal treatment outcomes. Further research could focus on improving diagnostic strategies and screening methods for cervical cancer in women with POP. Additionally, studies could explore the effectiveness of different treatment approaches and management strategies for women with both conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Wei Jiang for assistance with providing relevant professional images.

Funding: This study was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE and AME Case Series reporting checklists. Available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-19/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-19/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-19/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gpm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gpm-24-19/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Ethical approval was waived by the ethics committee as it was a retrospective case series and no patient identifiable information was used. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this article and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Boodoosingh R, Lima U, Fulu-Aiolupotea SM, et al. Lessons learned from developing a Samoan health education video on pelvic organ prolapse. J Vis Commun Med 2022;45:169-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ladd M, Tuma F. Rectocele. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Le NB, Rogo-Gupta L, Raz S. Surgical options for apical prolapse repair. Womens Health (Lond) 2012;8:557-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bacalbasa N, Halmaciu I, Cretoiu D, et al. Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer in Patients With Uterine Prolapse. In Vivo 2020;34:2073-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Evangelopoulou AE, Zacharis K, Balafa K, et al. Challenges in Diagnosis and Treatment of a Cervical Carcinoma Complicated by Genital Prolapse. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2021;2021:5523016. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chapman HL, Dholakia JJ, Marcrom S, et al. Treatment of Cervical Cancer Complicated by Advanced Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Case Report. Urogynecology (Phila) 2024;30:309-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Estevinho C, Portela Carvalho A, Pinto AR, et al. Complete pelvic organ prolapse associated with cervical cancer. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e239706. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duhan N, Kadian YS, Sangwan N, et al. Uterovaginal Prolapse and Cervical Cancer: A Coincidence or an Association. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery 2008;24:145-50. [Crossref]

- Menhaji K, Harvie HS, Cheston E, et al. Relationship Between Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Non-Human Papillomavirus Pap Smear Abnormalities. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2018;24:315-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wan OY, Cheung RY, Chan SS, et al. Risk of malignancy in women who underwent hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;53:190-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elbiaa AA, Abdelazim IA, Farghali MM, et al. Unexpected premalignant gynecological lesions in women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for utero-vaginal prolapse. Prz Menopauzalny 2015;14:188-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuo K, Fullerton ME, Moeini A. Treatment patterns and survival outcomes in patients with cervical cancer complicated by complete uterine prolapse: a systematic review of literature. Int Urogynecol J 2016;27:29-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kahn RM, Gordhandas S, Craig K, et al. Cervical carcinoma in the setting of uterovaginal prolapse: comparing standard versus tailored management. Ecancermedicalscience 2020;14:1043. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pardal C, Correia C, Serrano P. Carcinoma of the cervix complicating a genital prolapse. BMJ Case Rep 2015;2015:bcr2015209580. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dawkins JC, Lewis GK, Toy EP. Cervical cancer complicating pelvic organ prolapse, and use of a pessary to restore anatomy for optimal radiation: A case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2018;26:14-6. Erratum in: Gynecol Oncol Rep 2021;35:100703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rao K, Kumar NP, Geetha AS. Primary carcinoma of vagina with uterine prolapse. J Indian Med Assoc 1989;87:10-2. [PubMed]

- Luna P, Sanchez W. Vaginal evisceration following radiotherapy and surgery for cervico-uterine cancer. Report of a case. Ginecol Obstet Mex 1996;64:73-5. [PubMed]

- da Silva BB, da Costa Araújo R, Filho CP, et al. Carcinoma of the cervix in association with uterine prolapse. Gynecol Oncol 2002;84:349-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Batista TP, Morais JA, Reis TJ, et al. A rare case of invasive vaginal carcinoma associated with vaginal prolapse. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;280:845-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loizzi V, Cormio G, Selvaggi L, et al. Locally advanced cervical cancer associated with complete uterine prolapse. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:548-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cabrera S, Franco-Camps S, García A, et al. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer in prolapsed uterus. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2010;282:63-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim HG, Song YJ, Na YJ, et al. A case of vaginal cancer with uterine prolapse. J Menopausal Med 2013;19:139-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Li Q, Du H, et al. Uterine prolapse complicated by vaginal cancer: a case report and literature review. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2014;77:141-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vanichtantikul A, Tharavichitkul E, Chitapanarux I, et al. Treatment of Endometrial Cancer in Association with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2017;2017:1640614. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung CP, Lee SJ, Wakabayashi MT. Uterine and cervical cancer with irreducible pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:621-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Constantin F, Veit-Rubin N, Ramyead L, et al. Rouhier's colpocleisis with concomitant vaginal hysterectomy: an instructive video for female pelvic surgeons. Int Urogynecol J 2019;30:495-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cola A, Milani R, Buda A, et al. Surgical treatment of complete uterovaginal prolapse and concomitant vaginal cancer: a video case report. Int Urogynecol J 2020;31:1703-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacomina LE, Garcia MD, Santiago AC, et al. Chemoradiotherapy in a patient with locally advanced small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix complicated by pelvic organ prolapse: A case report. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2021;37:100832. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Onigahara M, Yanazume S, Ushiwaka T, et al. Importance of Cervical Elongation Assessment for Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther 2021;10:127-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee DH, Joo JK, Suh DS, et al. Successful treatment of locally advanced bulky cervical cancer complicated by irreducible complete uterine prolapse: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022;101:e28664. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Niu LN, Wang JX, Li X, et al. Clinical Analysis of the Discovery of Malignant Gynecological Tumors in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Front Surg 2022;9:877857. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ota Y, Suzuki Y, Matsunaga T, et al. New combined surgery for cervical cancer complicated by pelvic organ prolapse using autologous fascia lata: A case report. Clin Case Rep 2020;8:1382-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Wang Q, Wang W, et al. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising in adenomyosis in a patient with pelvic organ prolapse-case report. BMC Womens Health 2023;23:150. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andiman SE, Bui AH, Hardart A, et al. Unanticipated Uterine and Cervical Malignancy in Women Undergoing Hysterectomy for Uterovaginal Prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2021;27:e549-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mahnert N, Morgan D, Campbell D, et al. Unexpected gynecologic malignancy diagnosed after hysterectomy performed for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:397-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barakzai S, Koltun-Baker E, Melville SJF, et al. Rates of unanticipated premalignant and malignant lesions at the time of hysterectomy performed for pelvic organ prolapse in an underscreened population. AJOG Glob Rep 2023;3:100217. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mizrachi Y, Tannus S, Bar J, et al. Unexpected Significant Uterine Pathological Findings at Vaginal Hysterectomy Despite Unremarkable Preoperative Workup. Isr Med Assoc J 2017;19:631-4. [PubMed]

- Roman LD, Morris M, Eifel PJ, et al. Reasons for inappropriate simple hysterectomy in the presence of invasive cancer of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol 1992;79:485-9. [PubMed]

- Lourenço AV, Fregnani CM, Silva PC, et al. Why are women with cervical cancer not being diagnosed in preinvasive phase? An analysis of risk factors using a hierarchical model. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2012;22:645-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenblatt KA, Osterbur EF, Douglas JA. Case-control study of cervical cancer and gynecologic screening: A SEER-Medicare analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2016;142:395-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lerman C, Caputo C, Brody D. Factors associated with inadequate cervical cancer screening among lower income primary care patients. J Am Board Fam Pract 1990;3:151-6. [PubMed]

- Wang J, Andrae B, Sundström K, et al. Effectiveness of cervical screening after age 60 years according to screening history: Nationwide cohort study in Sweden. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002414. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ko KD, Park SM, Lee K. Factors associated with the use of uterine cervical cancer screening services in korean elderly women. Korean J Fam Med 2012;33:174-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walker S, Hamilton W. Risk of cervical cancer in symptomatic women aged ≥40 in primary care: A case-control study using electronic records. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017;26: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshida M, Jimbo H, Shirai T, et al. A clinicopathological study of postoperatively upgraded early squamous-cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2000;26:259-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng YF, Wang XY, Lü WG, et al. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2+ in low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion pathologically diagnosed by colposcopy-assisted biopsy. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2010;90:1882-5. [PubMed]

- Liegise H, Barmon D, Baruah U, et al. Reason for improper simple hysterectomy in invasive cervical cancer in Northeast India. J Cancer Res Ther 2022;18:1564-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Srisomboon J, Pantusart A, Phongnarisorn C, et al. Reasons for improper simple hysterectomy in patients with invasive cervical cancer in the northern region of Thailand. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2000;26:175-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Massad SL, Cejtin HE, Abu-Rustum NR. Presentation and screening history of indigent women with cervical cancer: implications for prevention. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2000;4:208-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reis BS, Nogueira CM, Meneses AFP, et al. Experiences of women with advanced cervical cancer before starting the treatment: Systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2023;161:8-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mesafint Z, Berhane Y, Desalegn D. Health Seeking Behavior of Patients Diagnosed with Cervical Cancer in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2018;28:111-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Umeononihu OS, Adinma JI, Obiechina NJ, et al. Uterine leiomyoma associated non-puerperal uterine inversion misdiagnosed as advanced cervical cancer: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2013;4:1000-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang L, Zhang M, Li K, et al. A real-world research of cervical cancer screening in patients diagnosed with cervical cancer by loop electrosurgical excision procedure. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2024;7:11. [Crossref]

- Zhu B, Wu Y, Huang J, et al. Massive prolapsed cervical lumps in cervical cancer treated with three-dimensional implant brachytherapy: a case report. Transl Cancer Res 2022;11:1440-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nemirovsky A, Horowitz AM, Malik RD. Patient counseling for pelvic organ prolapse surgery: methods used for patient education. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2023;6:20. [Crossref]

- Siddiqui NY, Gregory WT, Handa VL, et al. American Urogynecologic Society Prolapse Consensus Conference Summary Report. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2018;24:260-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dällenbach P. Anterior pelvic organ prolapse repair: the intersection of science and art. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2024;7:17. [Crossref]

Cite this article as: Waseem S, Lei Y, Luo S, Fang F, Wan L, Miao Y. Missed diagnosis of pelvic organ prolapse complicated with cervical cancer: a retrospective case series of five patients and review of literature. Gynecol Pelvic Med 2024;7:21.